Story and photos by Kristen Cart

My father, Jerry Osborn, and I had a rare opportunity this October to take a road trip. Our goals were to see family, check out our hunting camp, and see some of the sights in the west. Dad is in his eighties now, so we don’t put off any chances to do neat stuff. This trip exceeded our expectations. Happily, we also were able to take in some elevators.

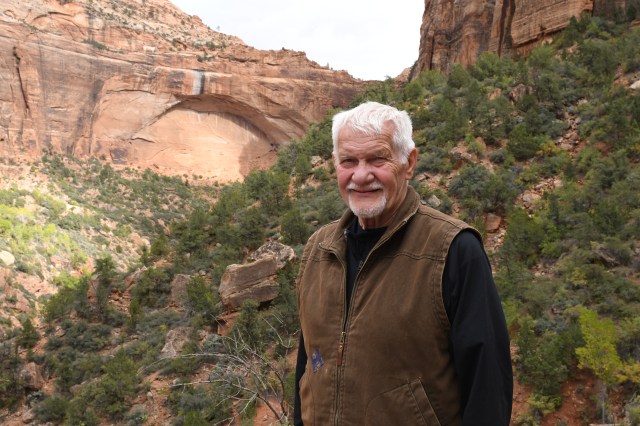

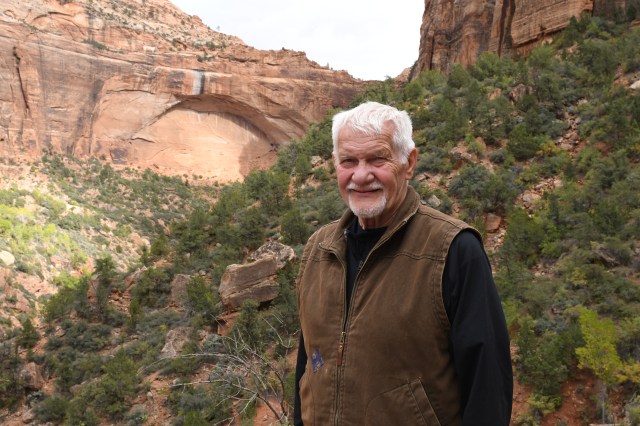

Jerry Osborn at Zion National Park, Utah

Our stop at the elevator in Limon, Colo., proved to be a wonderful surprise. There was a truck at the co-op when we arrived, but the office door was locked, so I approached the elevator itself and called out to see if it was deserted. When I turned around, a man was approaching from the office. I went to meet him.

Ed Owens was finishing up paperwork before going home for the night. I asked him about the history of the elevator, and he brought me into the office. Ed said his grandfather, S. L. Sitton, helped build the Limon elevator as well as the earlier, neighboring one in Genoa, Colo. He said his grandfather came into the area in 1939. He went away during the war, then came back and looked for whatever work he could find. Elevator construction provided a part-time laborer job that kept food on the table.

The builder put up the elevator like a layer cake, letting each concrete layer cure for a period before adding another, rather than by the continuous-pour method pioneered by early elevator construction companies. The Limon elevator was built in stages by farmers who built by day and farmed by night. I was impressed by Mr. Sitton’s fortitude, and I would have asked the old gentleman about it, but Ed said he was 97 years old and living in a nursing home in Flagler. He likely wouldn’t remember, and even if he did, he might not appreciate a visit.

The Genoa, Colo., elevator is in a neighboring town.

The best discovery was yet to come. When Ed ushered me into the office, he showed me the bronze plaque which originally adorned the driveway of the Limon elevator. Ed said all of the directors listed on the plaque were dead by now. The elevator was built in 1958, so all the community leaders of the time were long gone. But the key bit of information on the plaque was the name of the builder and designer, M. and A. Enterprises, Inc., of Denver.

I was very excited to see this name. The company was based in Denver, and the designer claimed to be the builder. Based on the design of the elevator, I had a strong suspicion of who that designer might have been. We now had a key piece of information.

Followers of this blog know that we have puzzled over a few mysteries while tracking our grandfathers’ elevators. The most difficult story to reconstruct, thus far, was how the Mayer-Osborn Construction Company met its demise.

The Denver-based enterprise lasted from 1949 until at least 1954, when my grandfather, William Osborn, apparently left the business. In the summer of 1954 he built the Blencoe, Iowa, elevator with the help of my dad, Jerry Osborn; by the summer of 1955, William was home from his Denver office and never worked elevator construction again. Meanwhile, his partner, Eugene Mayer, probably revived the company under various guises, but we know little of what became of him.

With our visit to Limon, Colo., we may have cracked the case.

Usually, the simplest explanation is the true one. The quickest way to explain why a thriving company would go away is to look for a disaster. Family lore says there was one. But I suspect the rumor of a collapsed elevator, lost to a crew that “shorted materials” and made bad concrete, might have been a tall tale that sprung from a much more pedestrian event. No such disasters can be found in 1954 or 1955 newspaper accounts.

The only related problem I could find occurred at the the Mayer-Osborn elevator in Blencoe, Iowa. During construction, when the elevator had reached about twelve feet high, the forms were slipped for the first time. As soon as concrete appeared below the slipped form, it began to slump and crumble. Bad concrete was indeed the culprit, and it necessitated a tear-down. To get back to a twelve foot height, the company had to add a day or two of expensive labor, which directly cut into profit. Could this event explain why William Osborn left the company? It’s the simplest explanation, so perhaps.

Several subsequent elevators bore the Mayer-Osborn manhole covers, but Dad didn’t know about these elevators, and he was certain that by 1955, his dad, William, was home for good.

The Mayer-Osborn elevator at McCook, Nebr. built in 1949

With its signature stepped headhouse, the elevator in Limon bears an uncanny resemblance to the first elevator Mayer-Osborn built in McCook, Neb. In fact, it is the same design, updated somewhat, and dated 1958. So it certainly went up after Grandpa left the business. But what about Eugene Mayer? Dad said that he was the designer, whereas Bill Osborn started as a carpenter and learned his construction skills on the job. Mayer still retained ownership of his elevator designs, which could explain why McCook clones continued to pop up all over the plains in the mid-1950s.

That brings us back to the builder of the Limon elevator, as inscribed on the plaque, “M. and A. Enterprises, Inc.” It seems inescapable that the “M.” was Mr. Eugene Mayer.

The Limon elevator had newer innovations but was built haltingly. Plainly, all was not the same as it had been when Bill Osborn was on the job. Perhaps fewer workers were available. Fewer contracts were awarded as subsidies waned. So the big, ambitious, day-and-night event of an elevator project was toned down somewhat. I expect we will find that Eugene Mayer’s design was eventually sold and others built it, then it passed into history, along with the great concrete elevator boom.

Happily, Limon’s elevator still thrives, and it gives us a peek at the amazing history of elevators on the American plains.

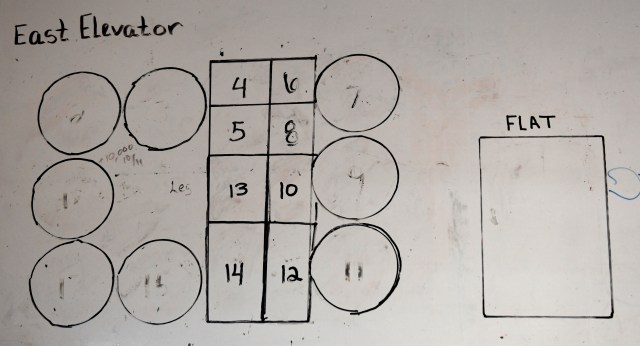

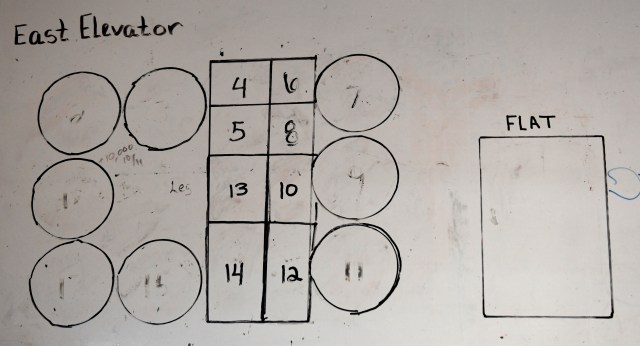

The layout of the elevator is used to record the content of each bin. Flat storage is adjacent to the concrete elevator.

A Tillotson crew put up a single-leg, 180,000-bushel, reinforced-concrete elevator in the seat of Butler County during one of the wettest periods ever recorded in the prairie region.

A Tillotson crew put up a single-leg, 180,000-bushel, reinforced-concrete elevator in the seat of Butler County during one of the wettest periods ever recorded in the prairie region. The elevator required 1,716 cubic yards of reinforced concrete, 20 yards of plain concrete for hoppers, and 81.16 tons of rebar.

The elevator required 1,716 cubic yards of reinforced concrete, 20 yards of plain concrete for hoppers, and 81.16 tons of rebar.

Nevertheless, we expected to see an elevator with a replacement structure at its crown.

Nevertheless, we expected to see an elevator with a replacement structure at its crown.

Theoretical leg capacity rated at 5,972 bushels per hour; actual capacity was 80 percent of theoretical, which rounded off to 4,780 (4,777.6) bushels per hour. This required just 22.3 horsepower.

Theoretical leg capacity rated at 5,972 bushels per hour; actual capacity was 80 percent of theoretical, which rounded off to 4,780 (4,777.6) bushels per hour. This required just 22.3 horsepower.

The first was at Cedar Bluffs, a village of 600 overlooking the Platte River. The Farmers Union Cooperative Association location was quiet when we arrived around 9.30 a.m., so we invited ourselves to walk the site and take photos.

The first was at Cedar Bluffs, a village of 600 overlooking the Platte River. The Farmers Union Cooperative Association location was quiet when we arrived around 9.30 a.m., so we invited ourselves to walk the site and take photos.