By K O Cart

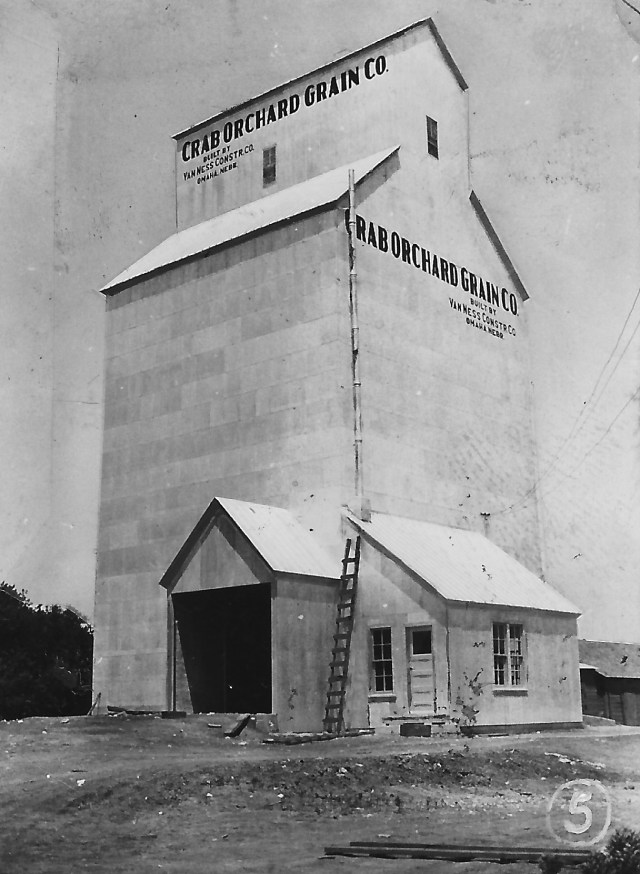

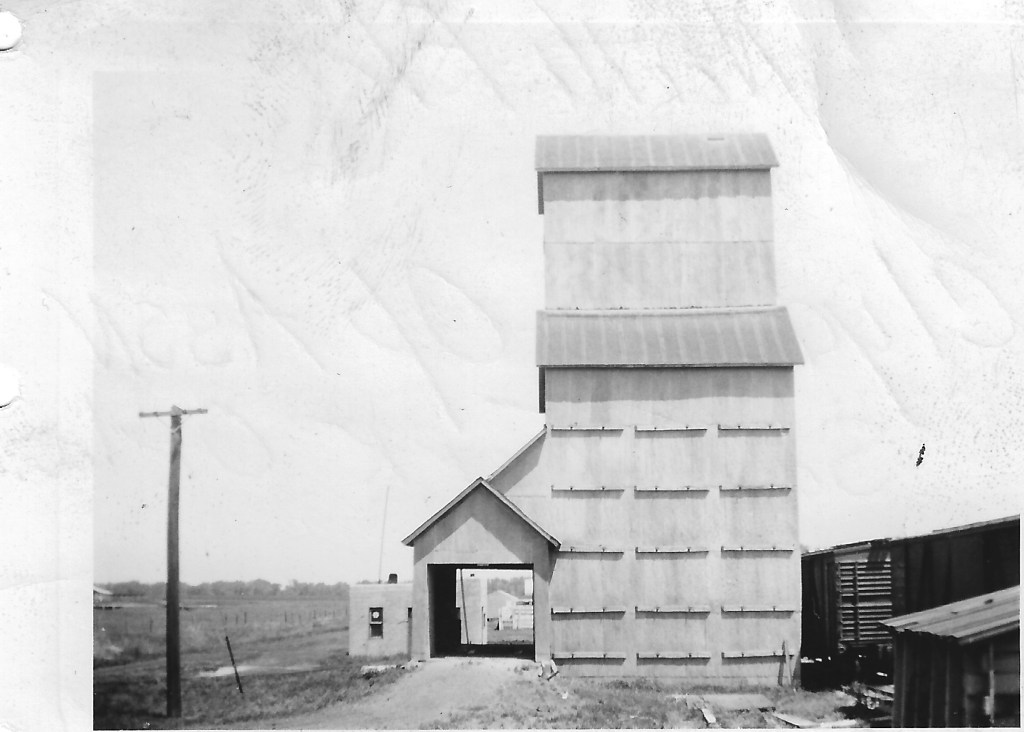

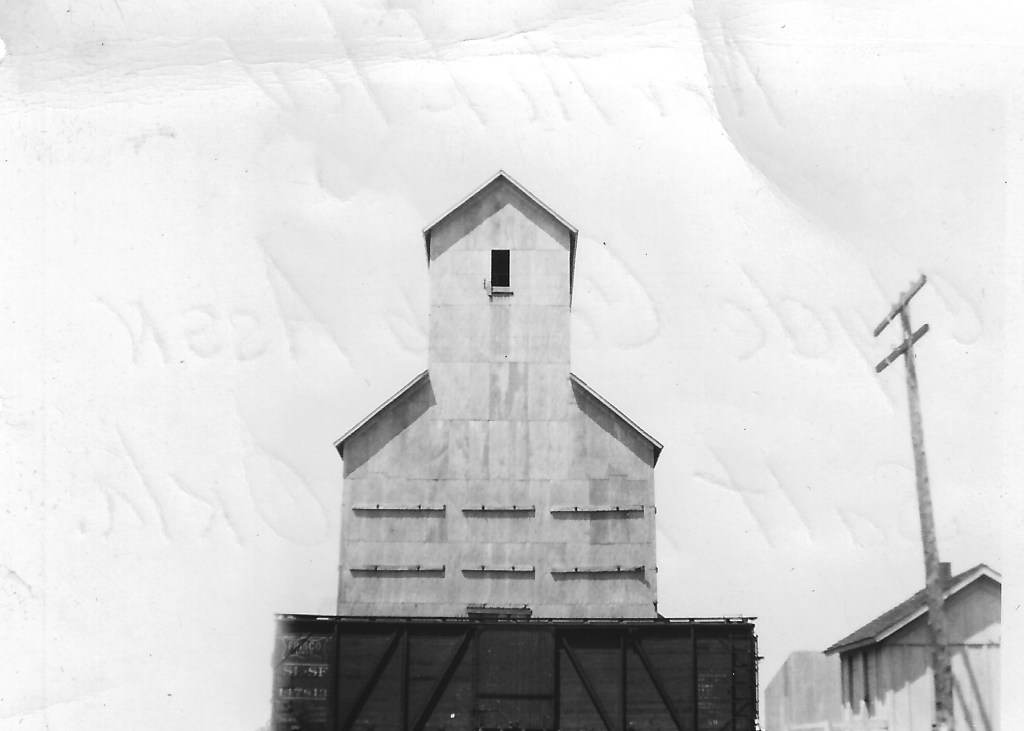

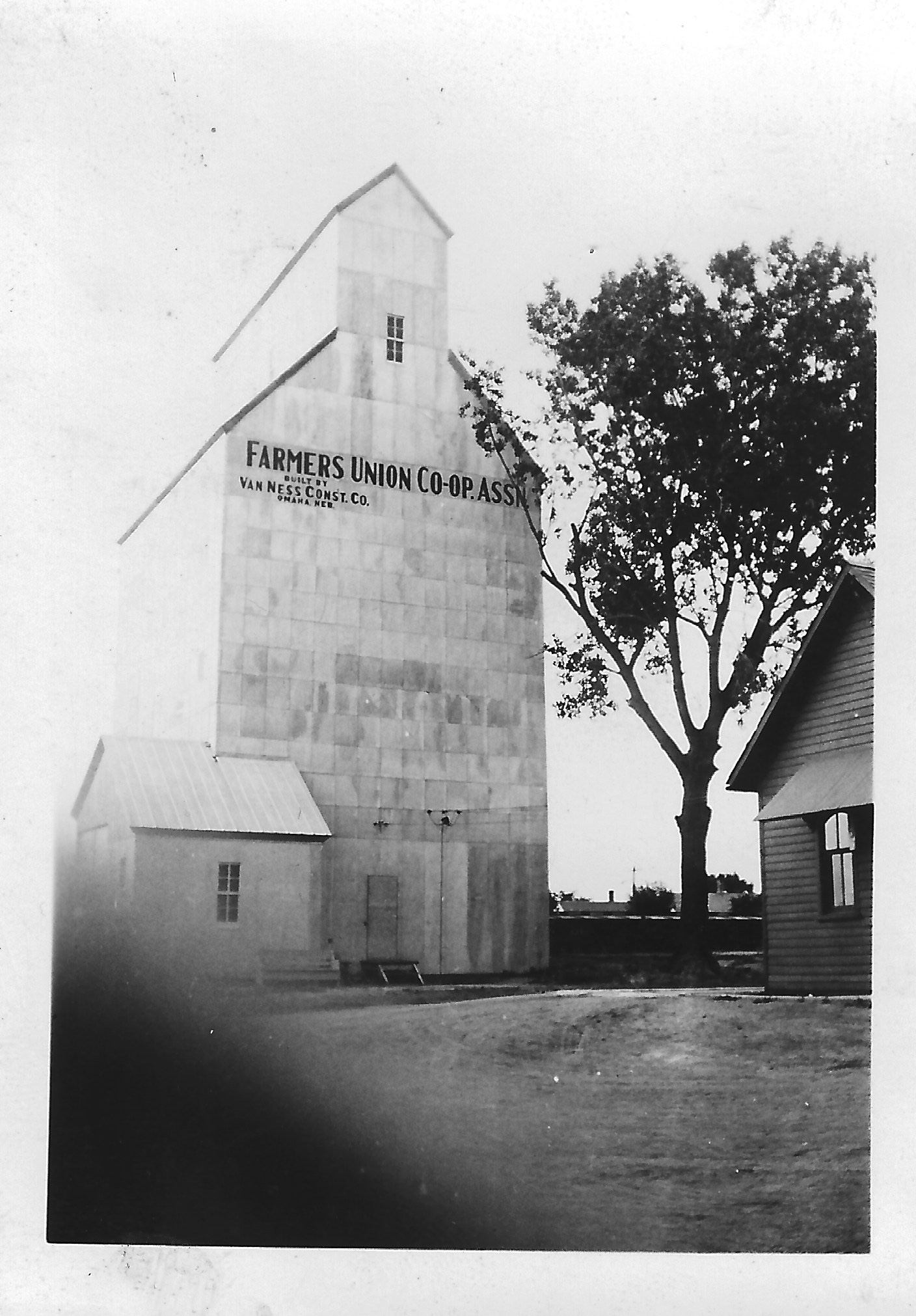

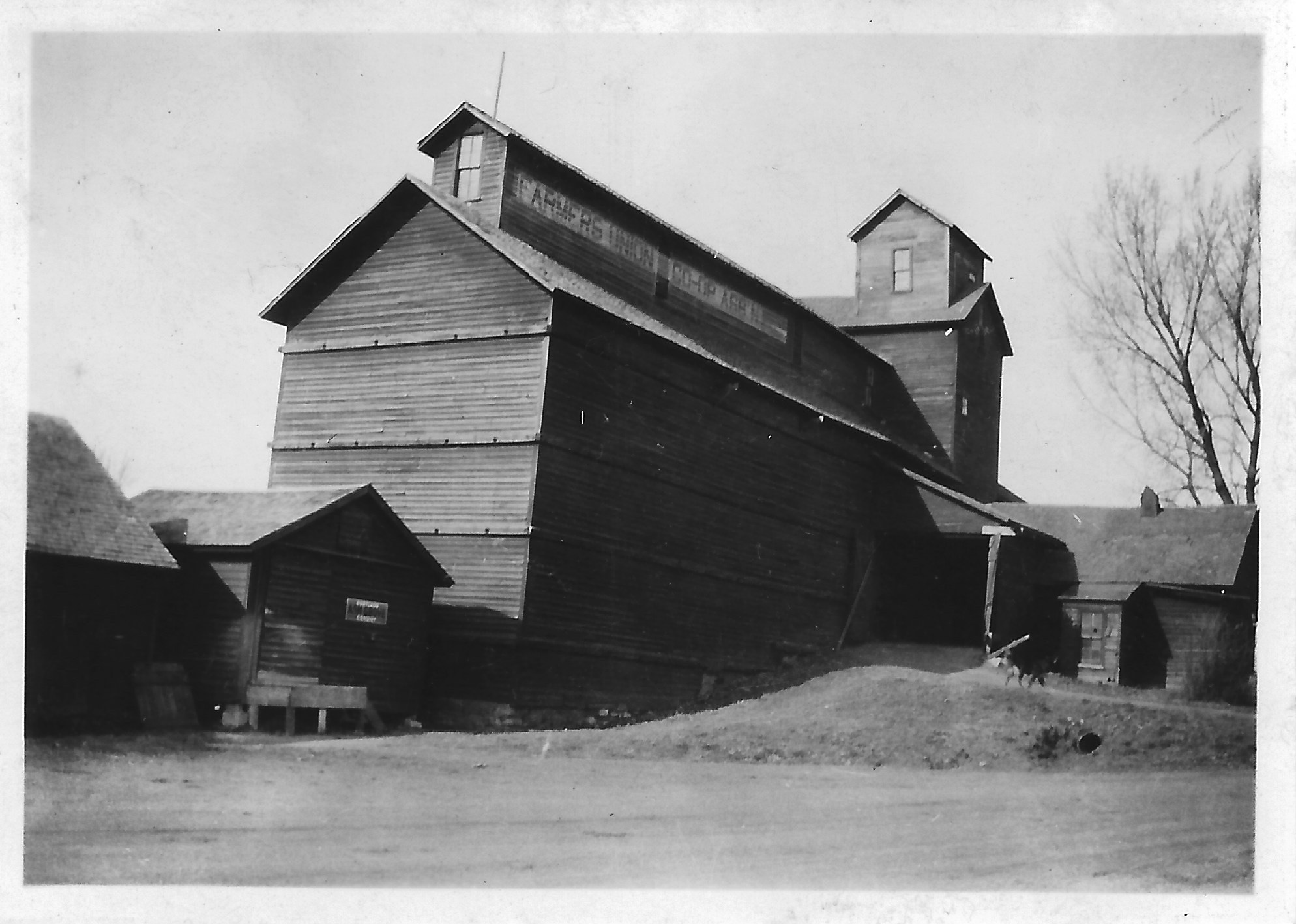

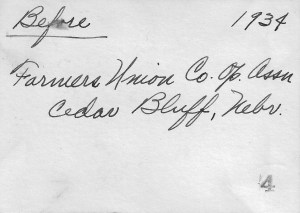

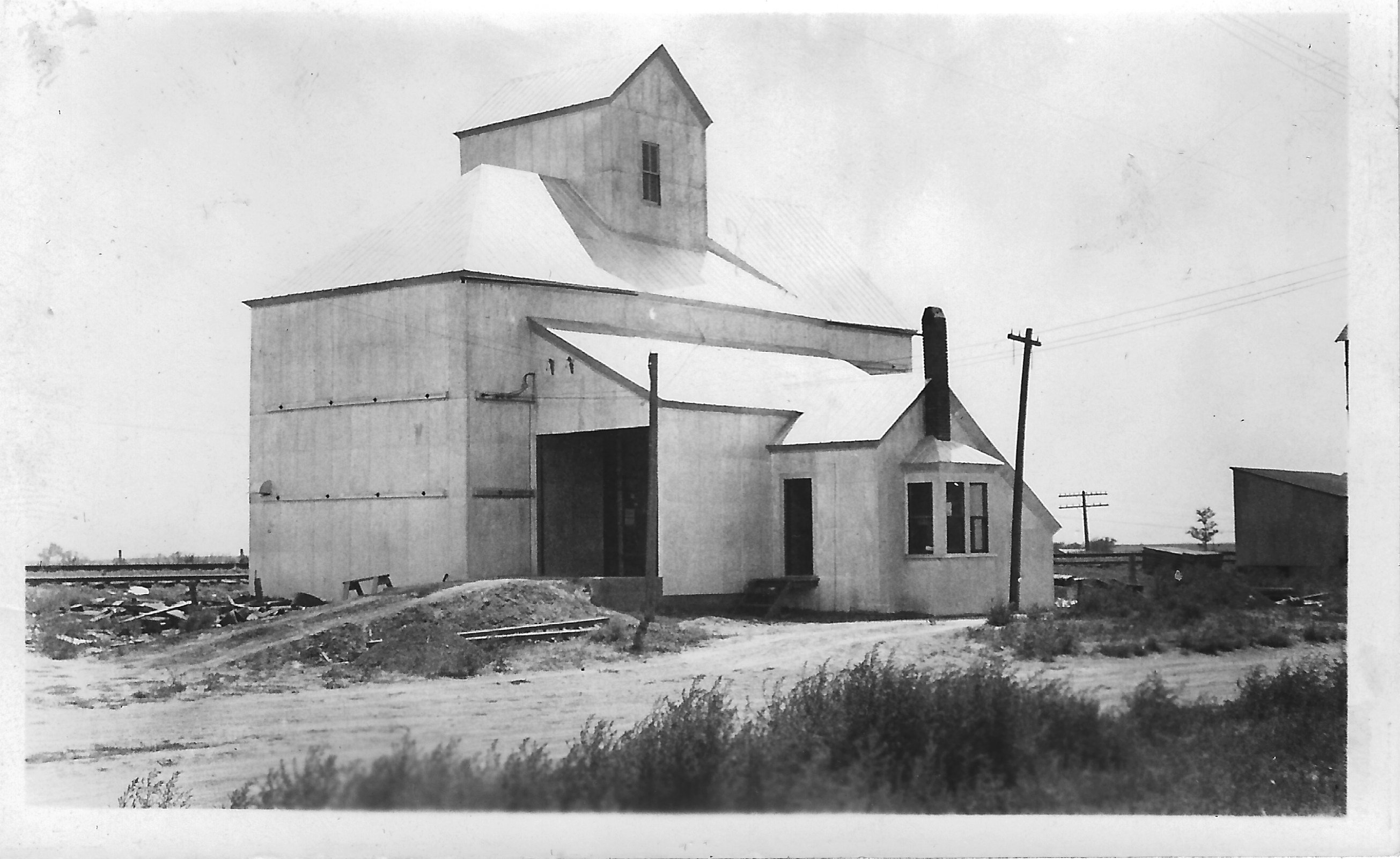

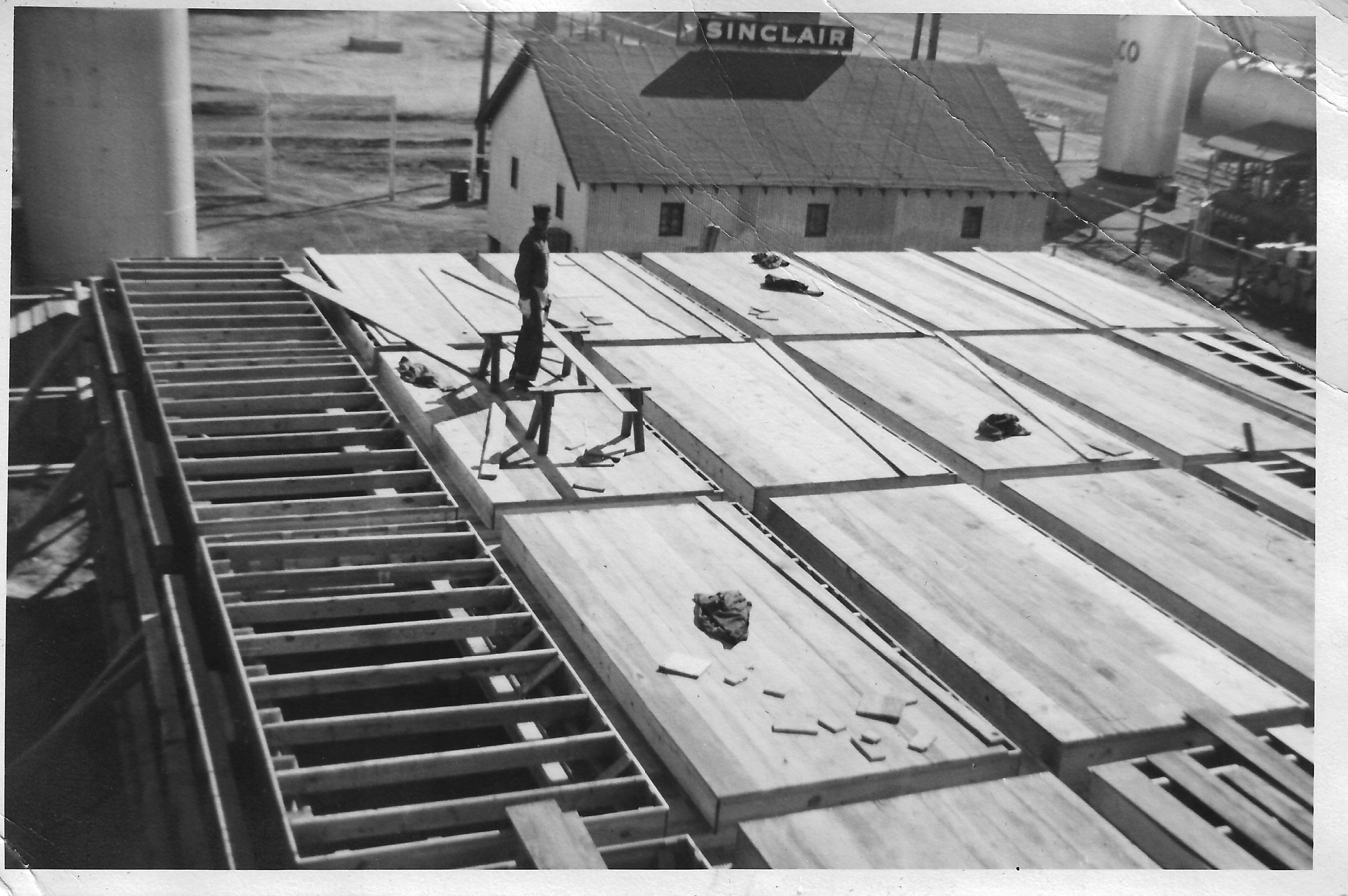

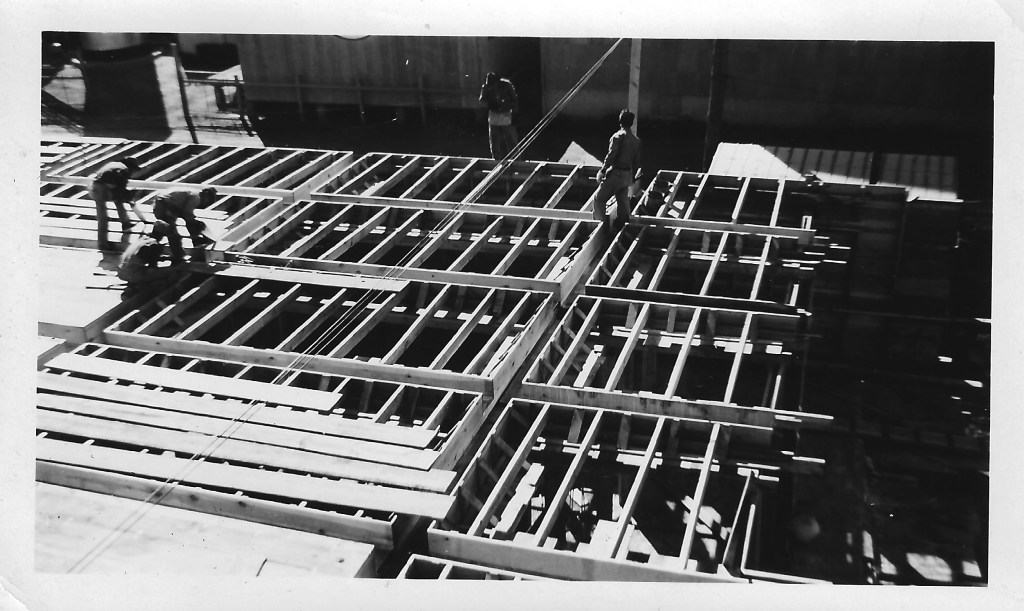

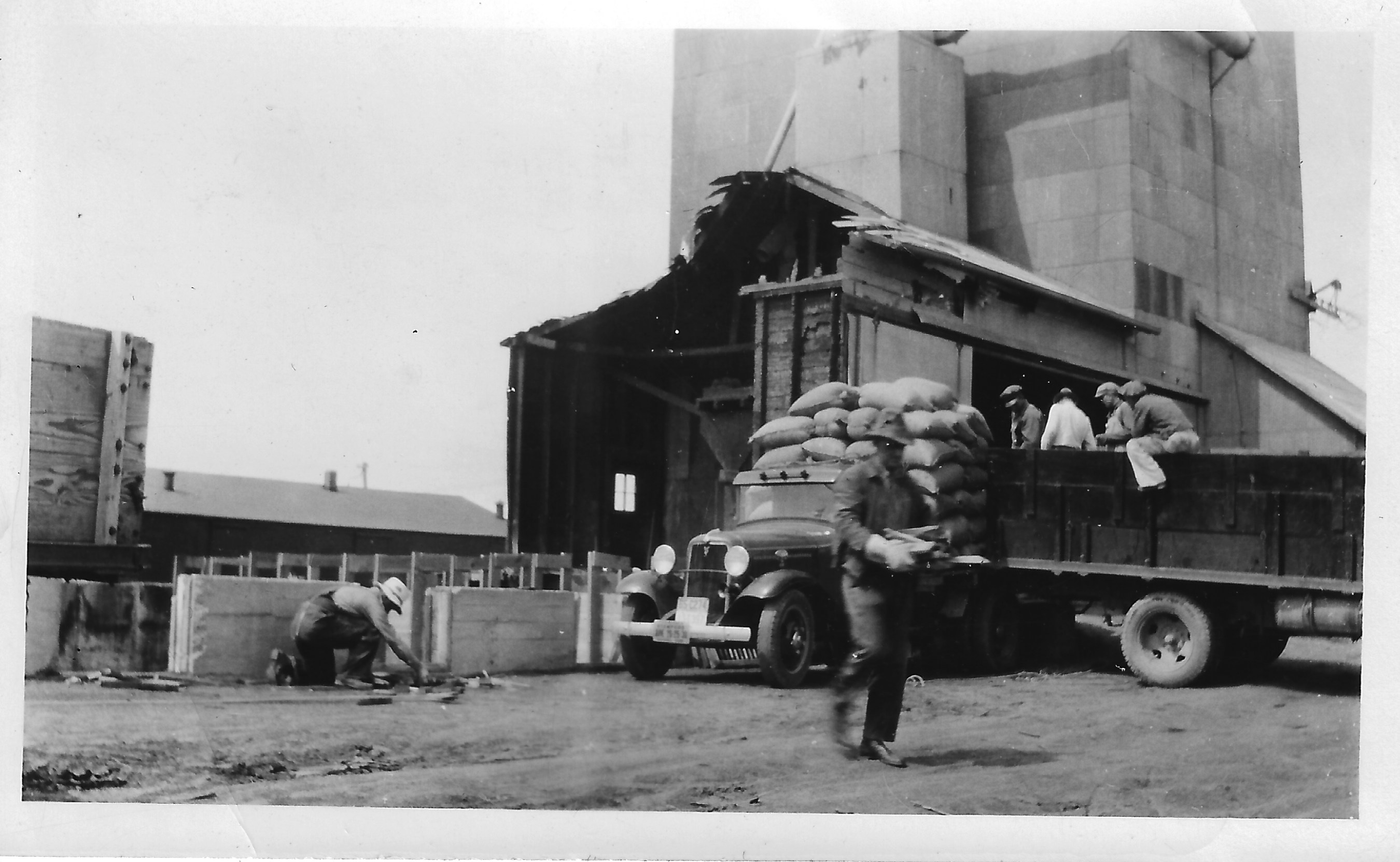

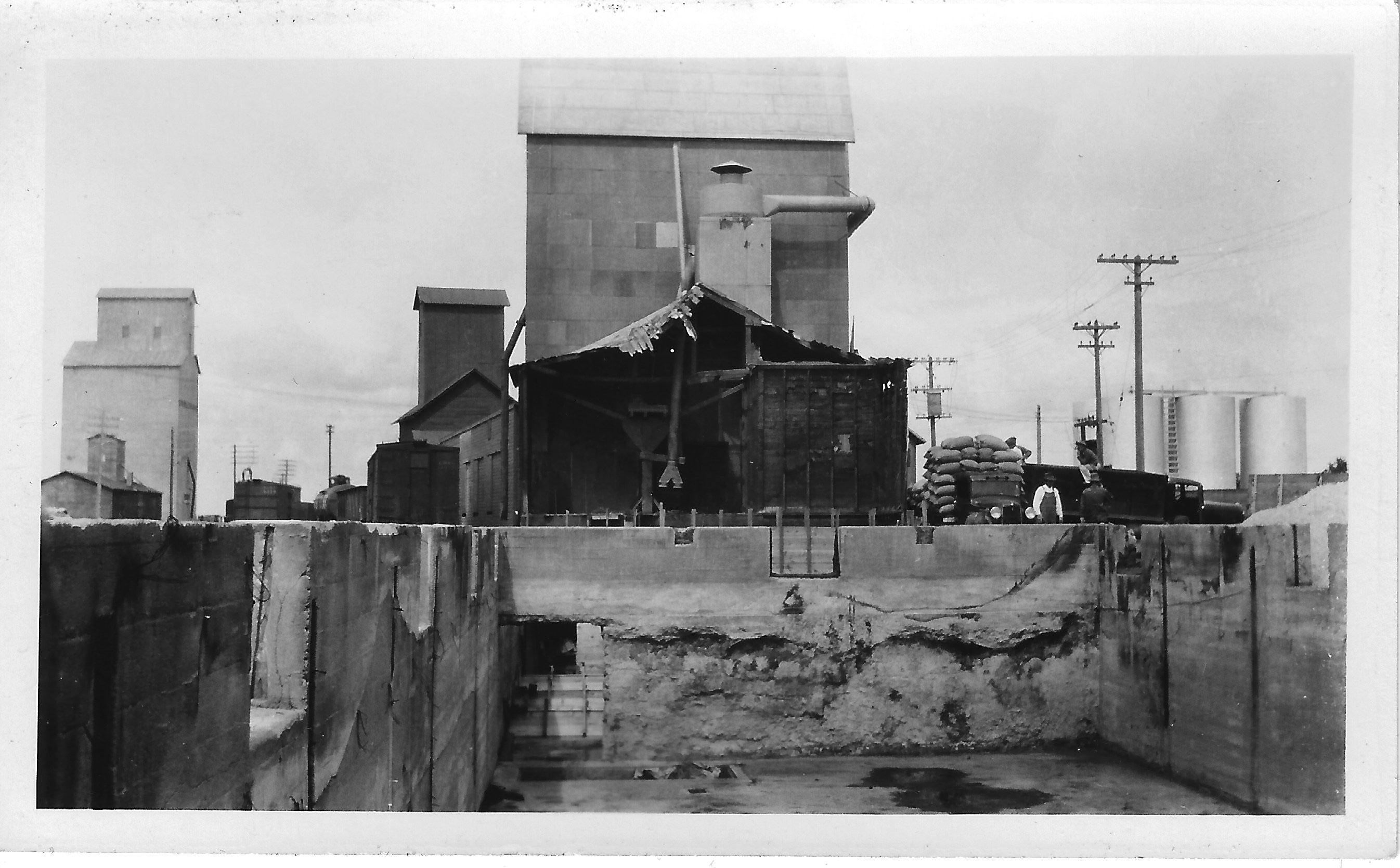

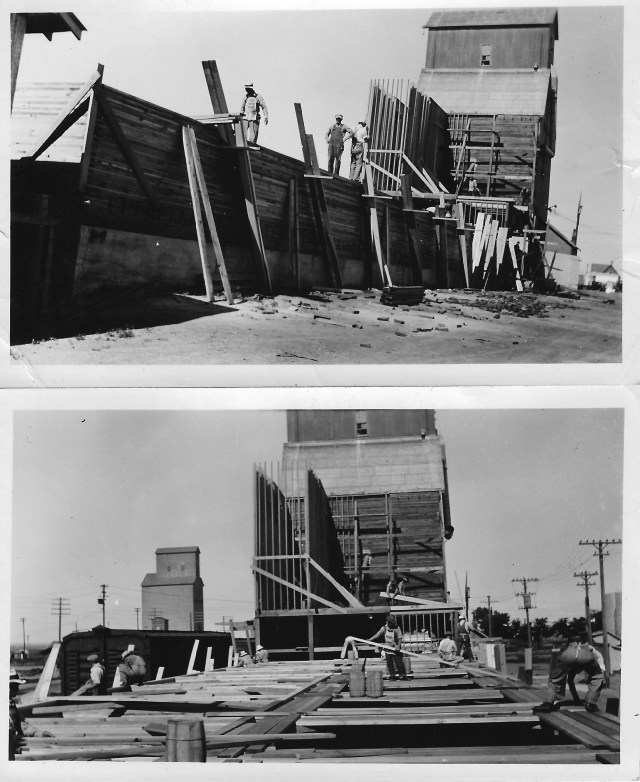

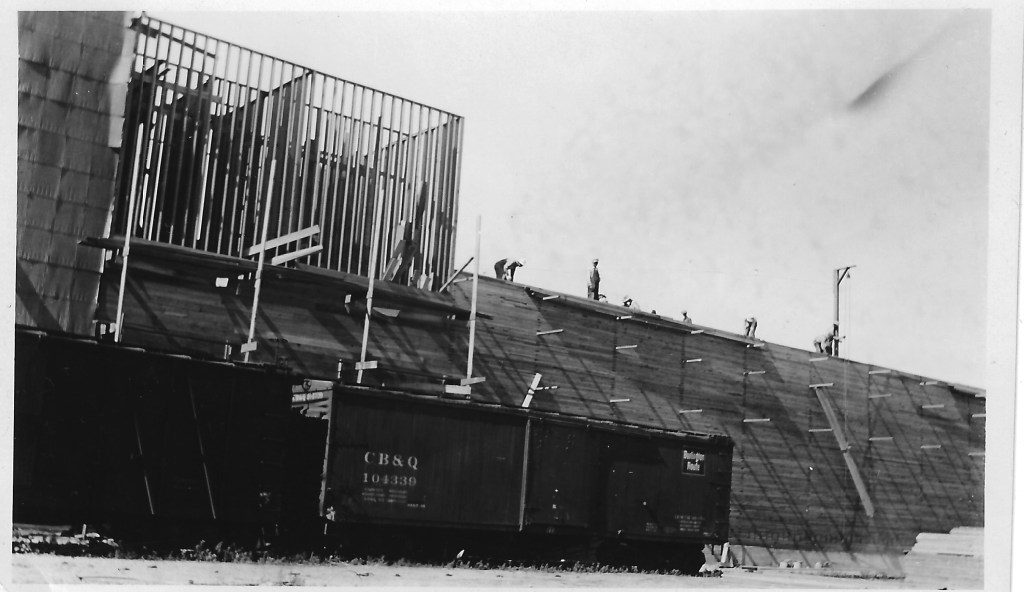

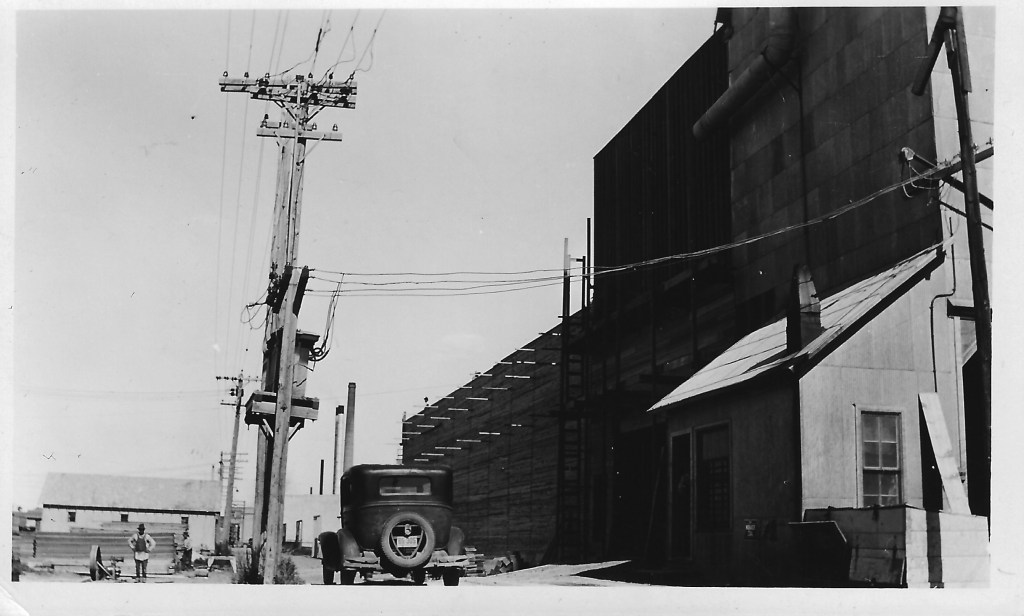

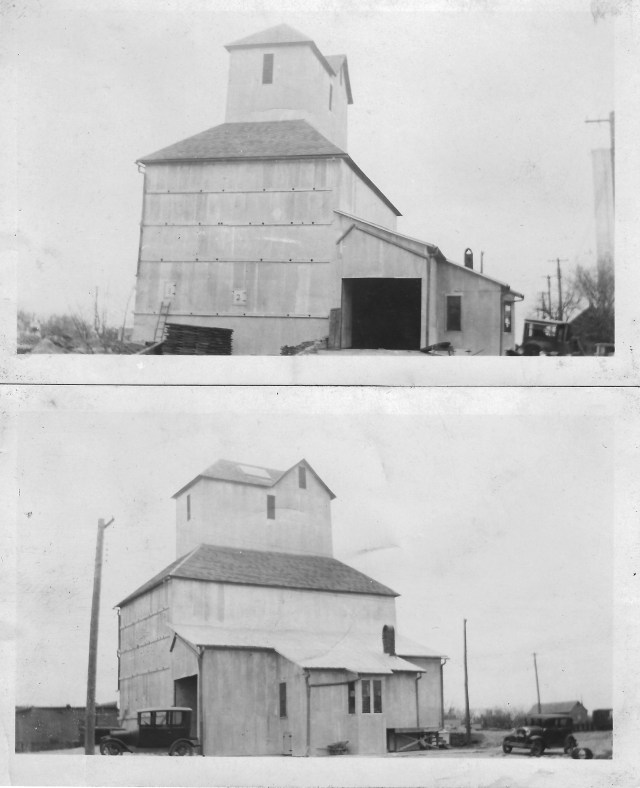

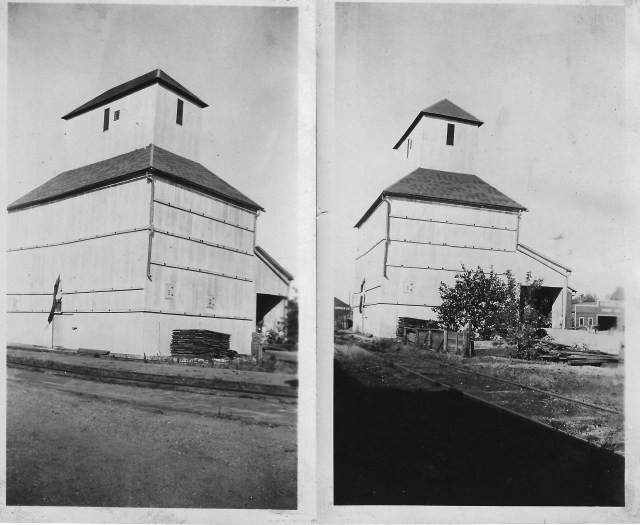

When my blogging partner Ronald Ahrens received a cache of photos from his grandfather’s estate, he discovered pictures of the construction of an elevator annex in Alliance, Nebr., as indicated by handwritten captions. I searched my old elevator photos and found this 2016 image from my stop in Alliance on a trip through Nebraska. Details of the old headhouse were an exact match to the Van Ness Construction photos from Alliance, which Ronald featured in an earlier post on this blog.

I decided to revisit the site in February to see if the elevator and annex were still standing. We were in luck.

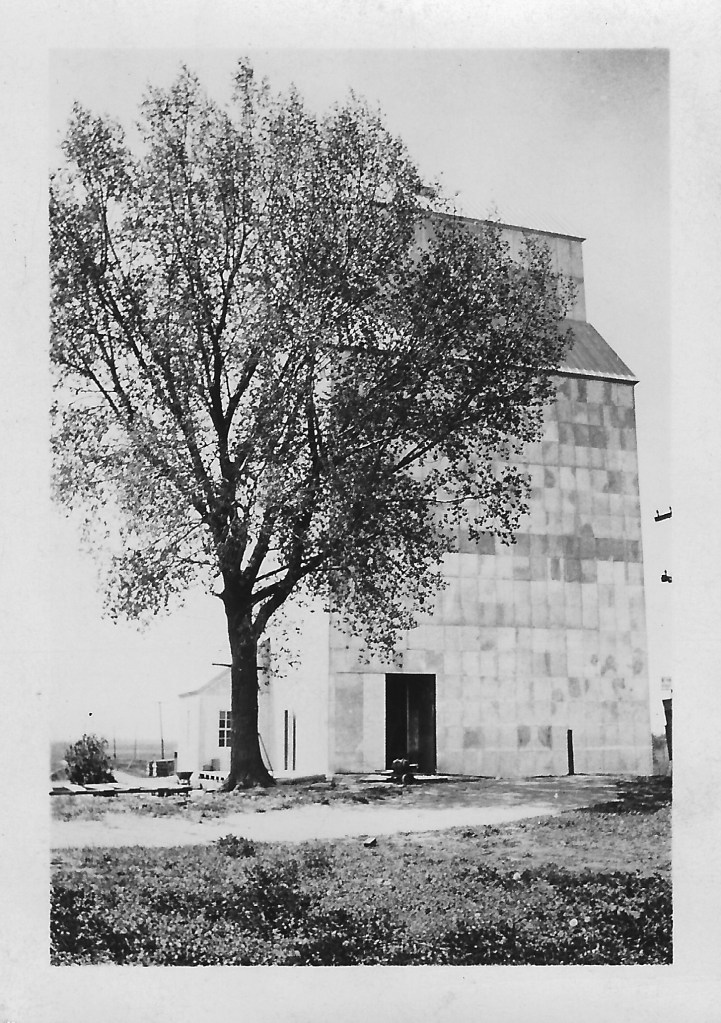

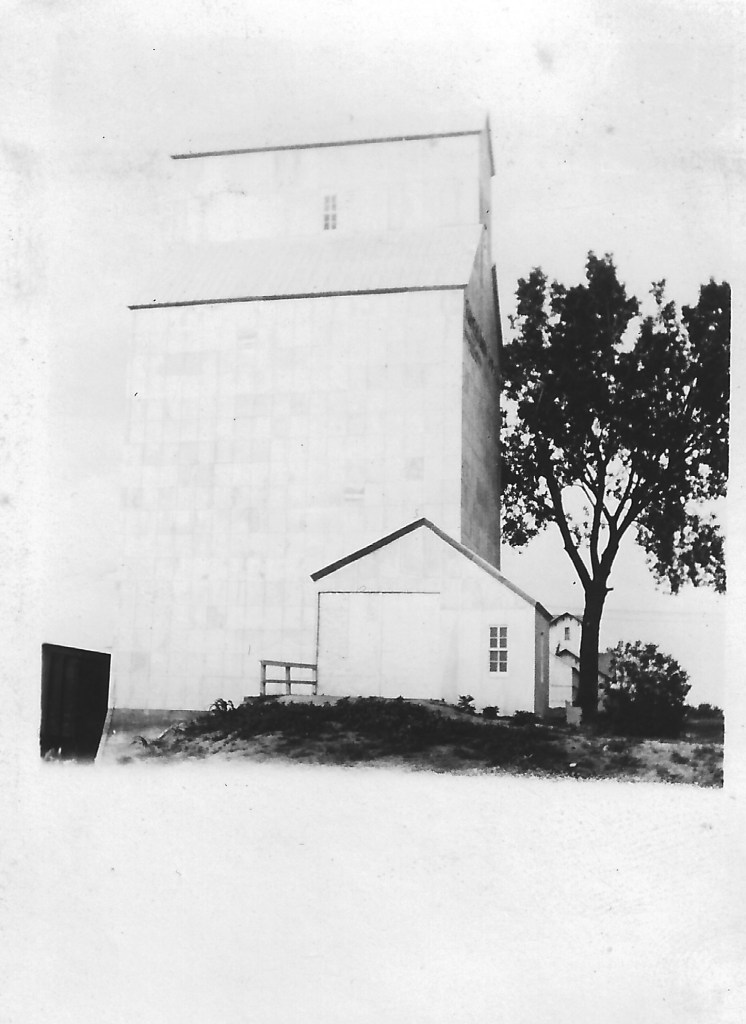

With the passage of another decade, the elevator (pictured above in my photo) looks more tattered and plainly unused, but it stands much the same as in this image. A local man who worked nearby said that owls lived in the headhouse, and they might come out in the evening, if I wanted to see them. I didn’t have time to stay until nightfall to find out. Otherwise, all was quiet. The annex had been quite a grand affair when first built, and was solidly constructed. It had not changed very much at all from the outside in nearly one hundred years.

I researched newspaper articles about Van Ness Construction and found that they repaired, updated, and also demolished elevators in the 1920s and 30s. Their niche in elevator construction fell somewhere between the first elevator pioneers and the builders of the concrete era. It is highly unlikely that many of the first-generation elevators survive, since new technology rapidly overtook them, and many of the Van Ness-period elevators are also gone. It was quite a shock to find one of their projects still standing.

To discover a Van Ness elevator that still exists, I start with a newspaper search to find a location, then check a Google satellite view to decide whether a visit is warranted. I also check my photo archives. So far, I have found only one, which, having dodged almost a century of tornadoes and the wrecking ball, is rather amazing to find. The Alliance annex holds the title as the only known remnant of decades of work by the Van Ness Construction Company. The title will stand, until we dig up another one.