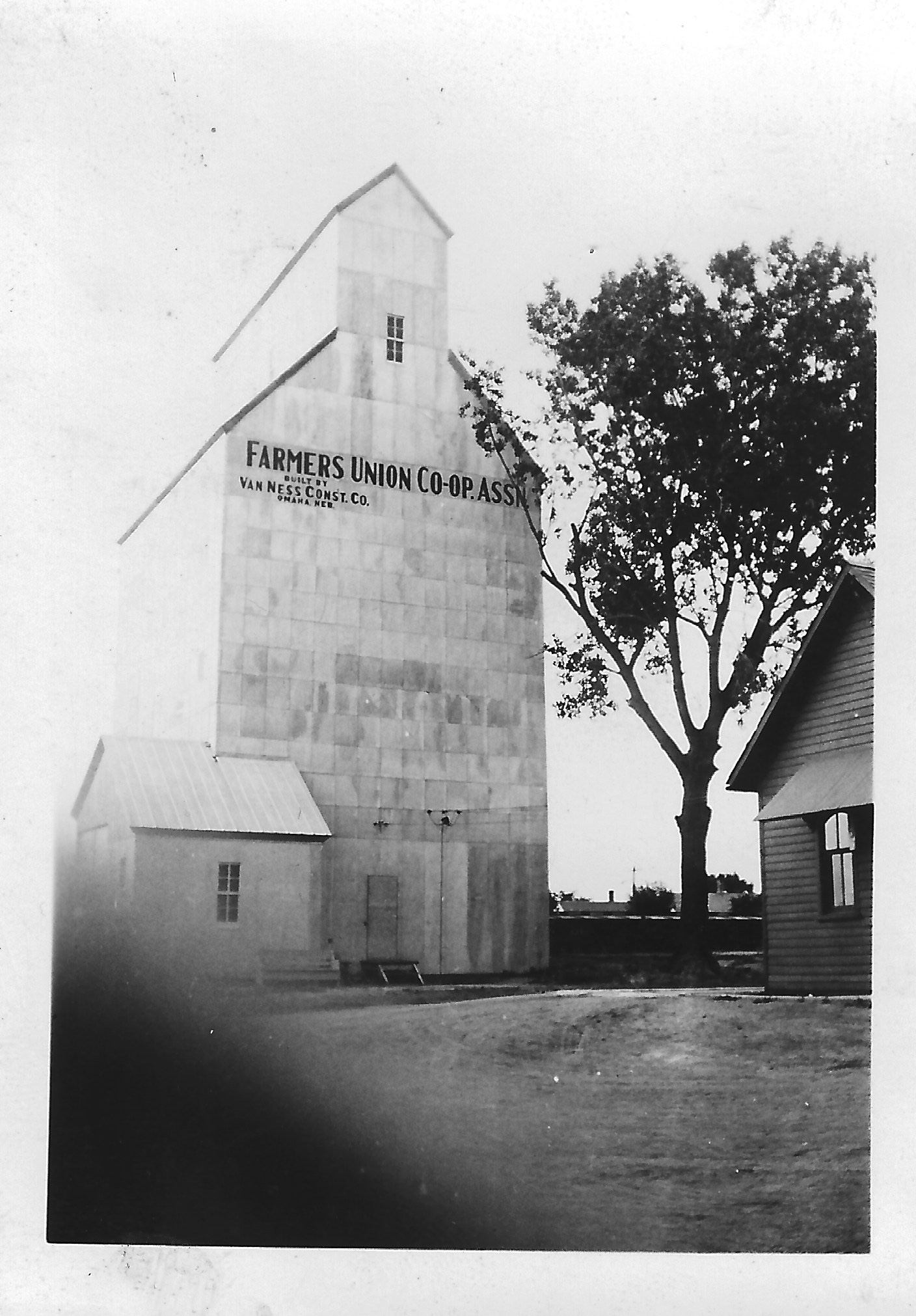

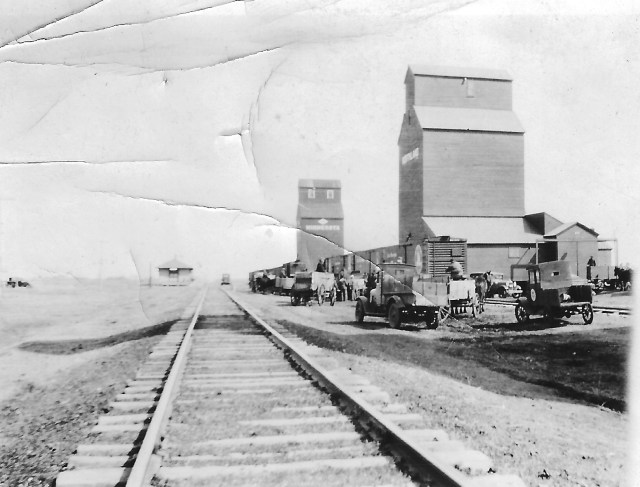

A lovely Monday in early May of 1934 proved perfect for festivities that attended dedication of the new Farmers Union elevator in Cedar Bluffs, Nebr.

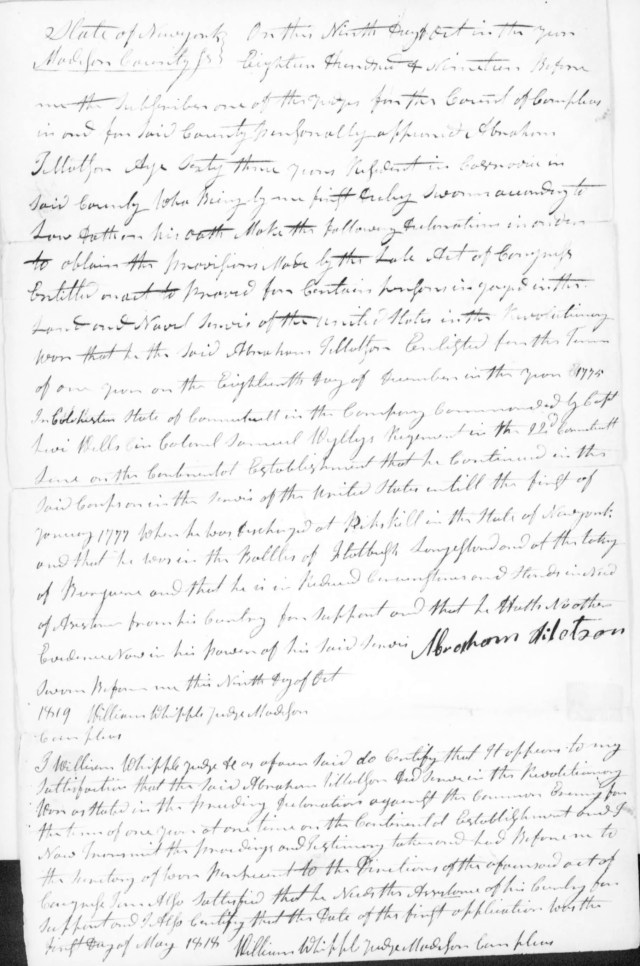

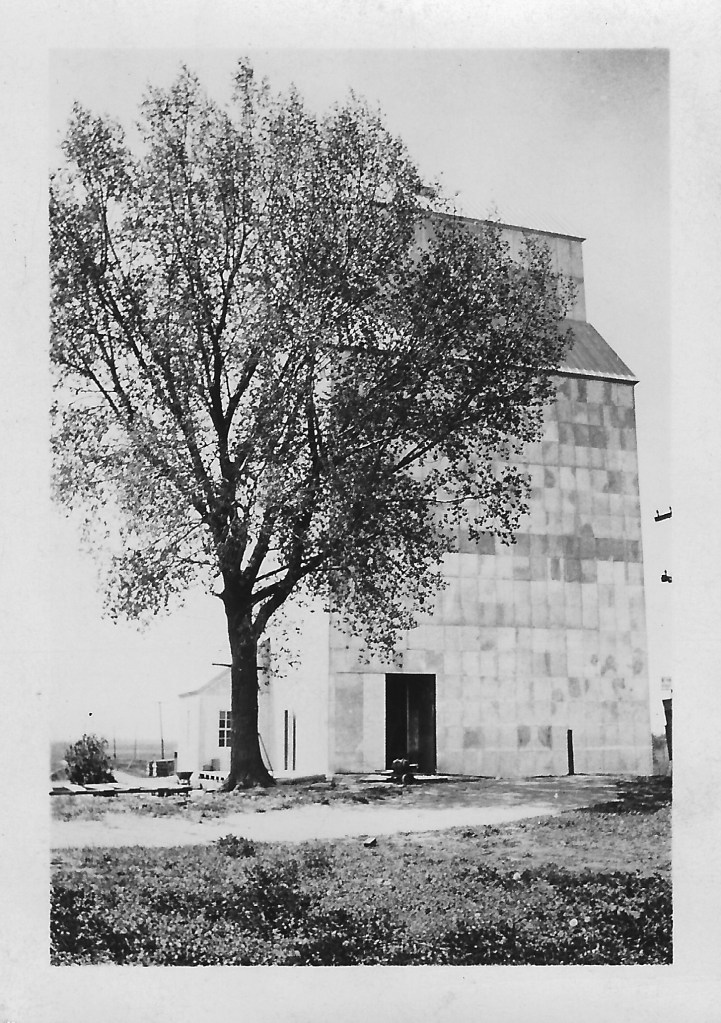

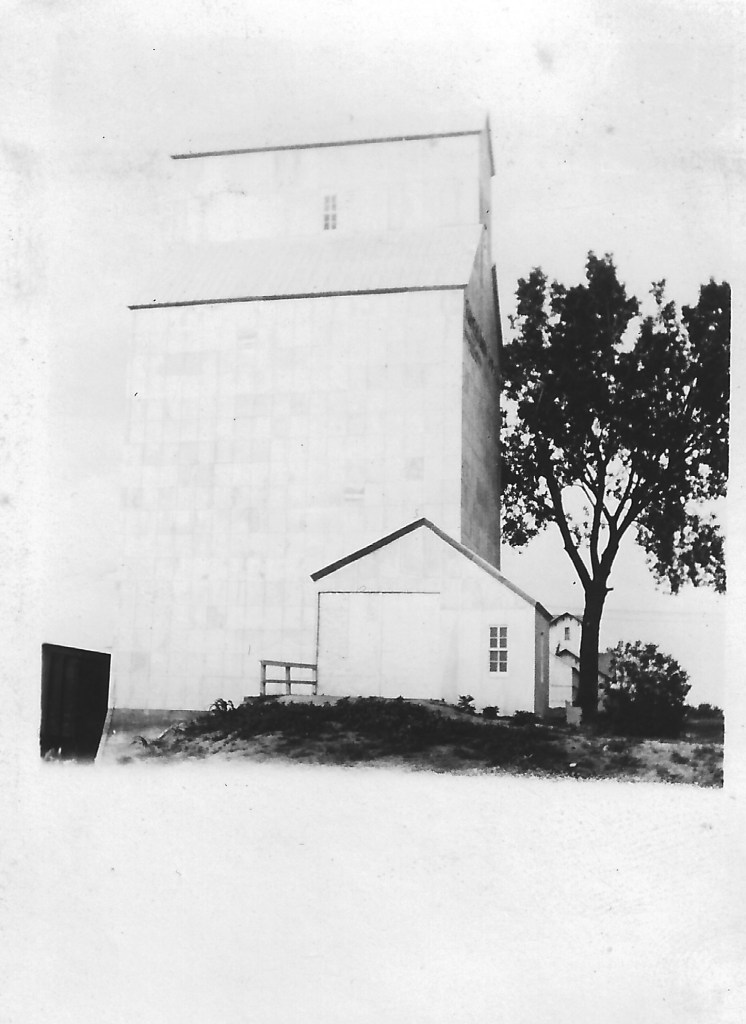

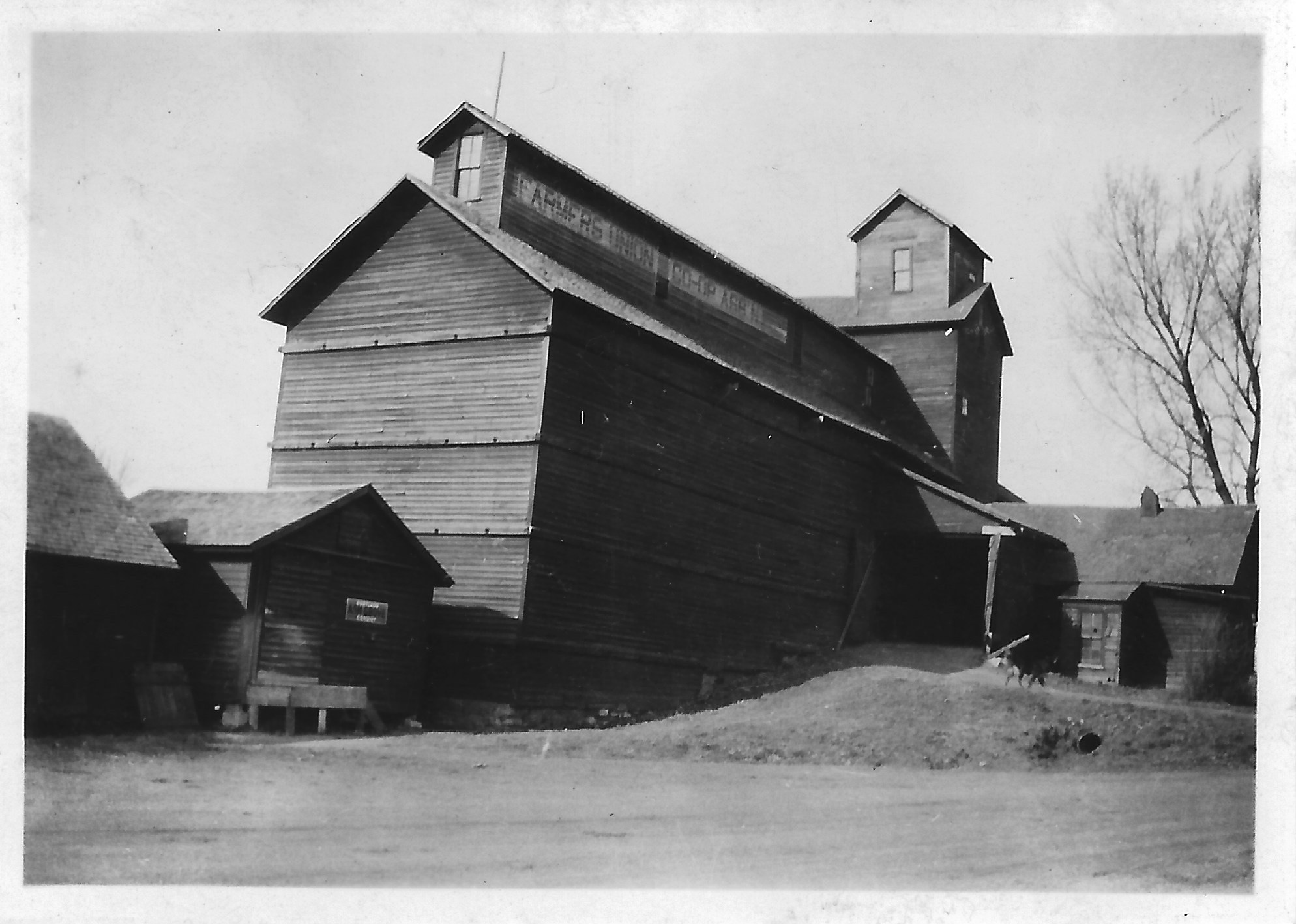

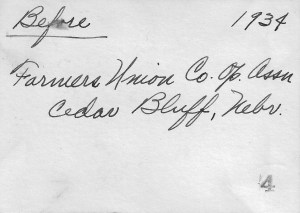

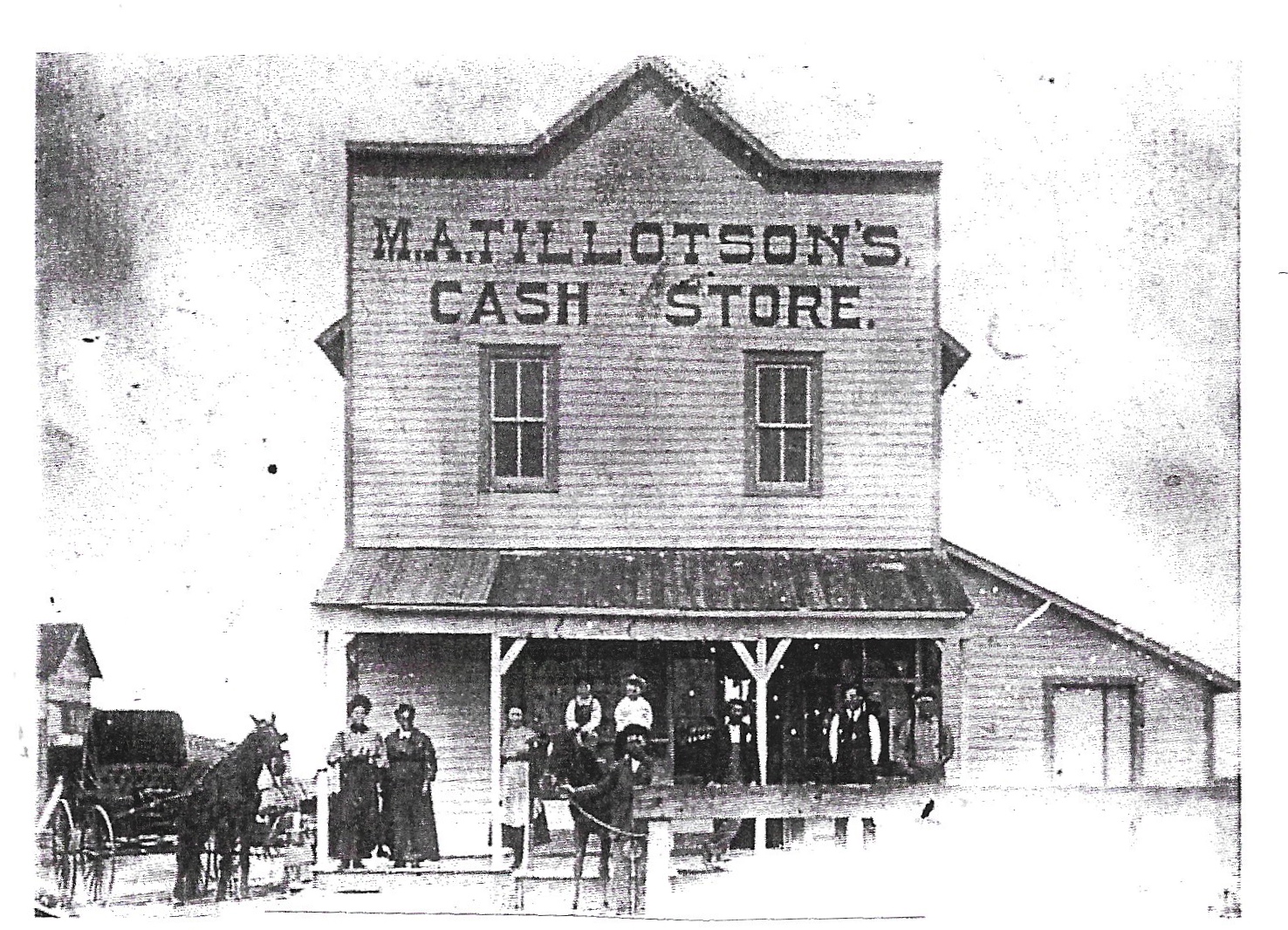

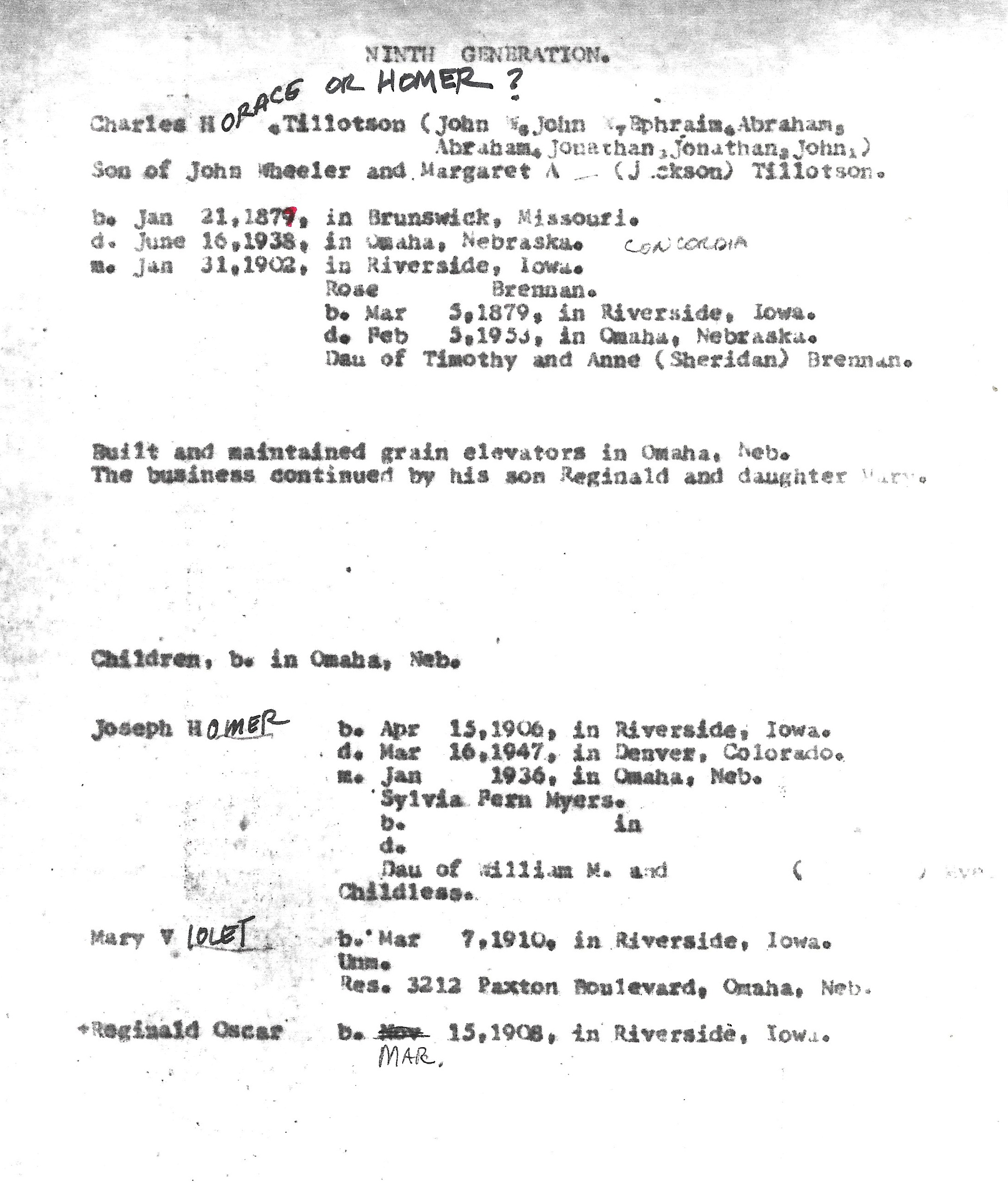

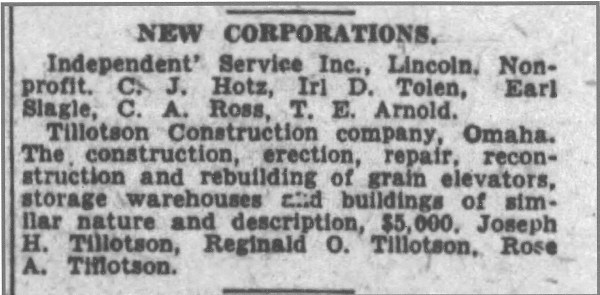

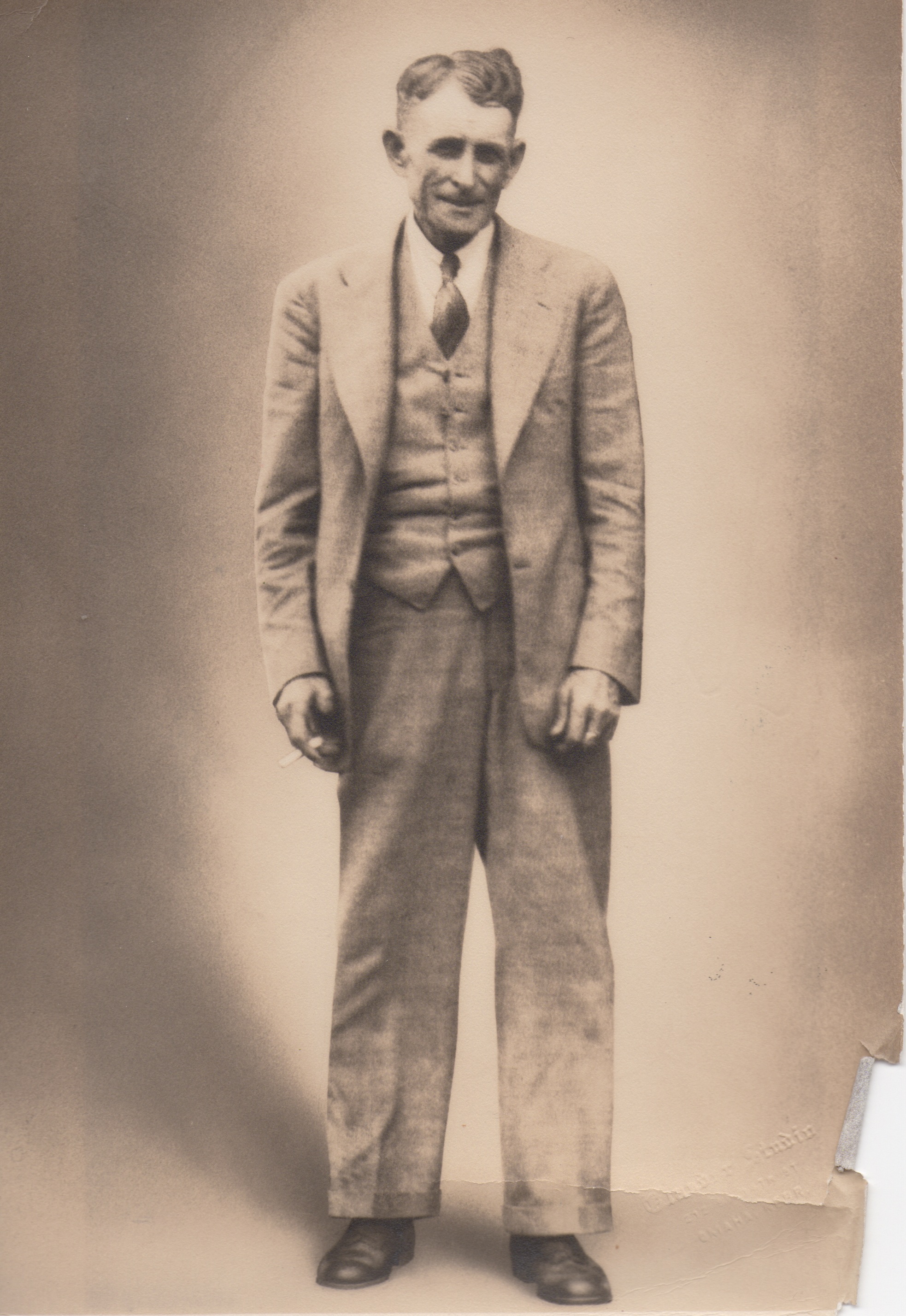

After deciding in January to tear down its 48-year-old elevator and rebuild, the Farmers Union Co-Operative Association awarded the job to Van Ness Construction Co., of Omaha. A new 30,000-bushel elevator soon rose on the same site as the demolished elevator in Cedar Bluffs, a progressive Saunders County village. Photos by Reginald Tillotson, who worked for Van Ness along with his father Charles H. Tillotson, show the job starting in early spring before the trees budded out.

A news report explains how the dedication attracted an “immense” crowd and sparked a festival-like atmosphere on that pleasant occasion. Events started at 12.00 noon with free ice cream, cake, and coffee for more than 600 registrants.

“There was plenty to eat for everybody,” the New Cedar Bluffs Standard reported.

After dinner, races and contests were held for boys and girls, providing entertainment for the crowd and fun for the youngsters. Cash prizes were given out. The Midland College band traveled from nearby Fremont to play for everybody.

Mayor J. P. Jessen took the platform, welcomed folks, and introduced lots of dignitaries. H.D. Black received special recognition as manager of the elevator, and Alex McAuley—a 17-year veteran of the company—was assistant manager.

Next came the parade. A line of automobiles carried the officers and directors of the elevator association. A former employee of Farmers Union weighed in with the ceremonial first load of wheat to be received and stored away in the new house.

The entertainment continued as a quartet took the stage and sang old favorites. Following their numbers, a solo vocalist performed with piano accompaniment.

Other cash prizes were awarded, this time to L.A. Freeman, the association stockholder who had the largest family present. The jackpot for longest distance traveled went to Jim Broz, who made the journey from Prague, a town 16.5 miles away by road.

Speechifying was courtesy of Newton Gaines, of the University of Nebraska Extension service, who “as usual did a mighty fine job of it. He is an interesting and entertaining speaker.” Gaines himself was Midland College graduate devoted to the gospel of better farming and spread it with humor and philosophy in thousands of speeches.

The Cedar Bluffs day of parties ended with a free, well-attended dance at the opera house, and the next day was back to normal with the new elevator in service. The dedication day was long-remembered by the people. Even now we take away the message of an elevator’s importance within its community. Sometimes in daily life, the people came and went without even noticing it, but in fact it was the thing that held the community together.

Concordia, Kan.

Concordia, Kan.

“When they moved from place to place with the construction company they had many funny places for a home. Your grandfather moved ten times one school term. They built cribbed elevators during those days. This was made by placing a two by four on a two by four to build the walls for the outside and to make the bins. The fields of corn and grain were used by the farmers so they had no great need for storage or grain elevators. So many jobs were to add on to bins or repair them. This made small jobs and many changes in places to live.

“When they moved from place to place with the construction company they had many funny places for a home. Your grandfather moved ten times one school term. They built cribbed elevators during those days. This was made by placing a two by four on a two by four to build the walls for the outside and to make the bins. The fields of corn and grain were used by the farmers so they had no great need for storage or grain elevators. So many jobs were to add on to bins or repair them. This made small jobs and many changes in places to live.

Uncle Charles notes that in the mid-1930s Reginald and Margaret lived with the elder Tillotsons at 624 N. 41st Street. They towed a travel trailer to job sites. In early July of 1936 they would also have towed along Uncle Charles, then 18 months old, and my mother Mary Catherine, who was nearly five months old.

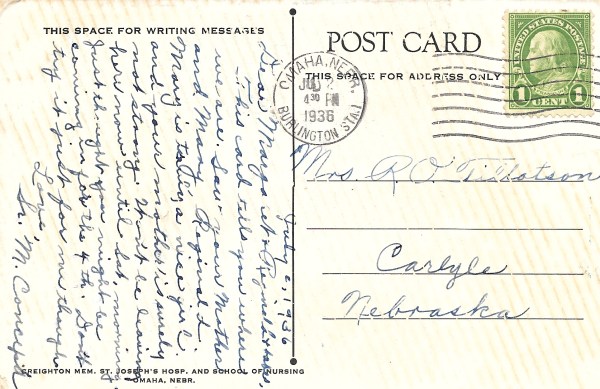

Uncle Charles notes that in the mid-1930s Reginald and Margaret lived with the elder Tillotsons at 624 N. 41st Street. They towed a travel trailer to job sites. In early July of 1936 they would also have towed along Uncle Charles, then 18 months old, and my mother Mary Catherine, who was nearly five months old. The USGS gives coordinates for Carlisle on its

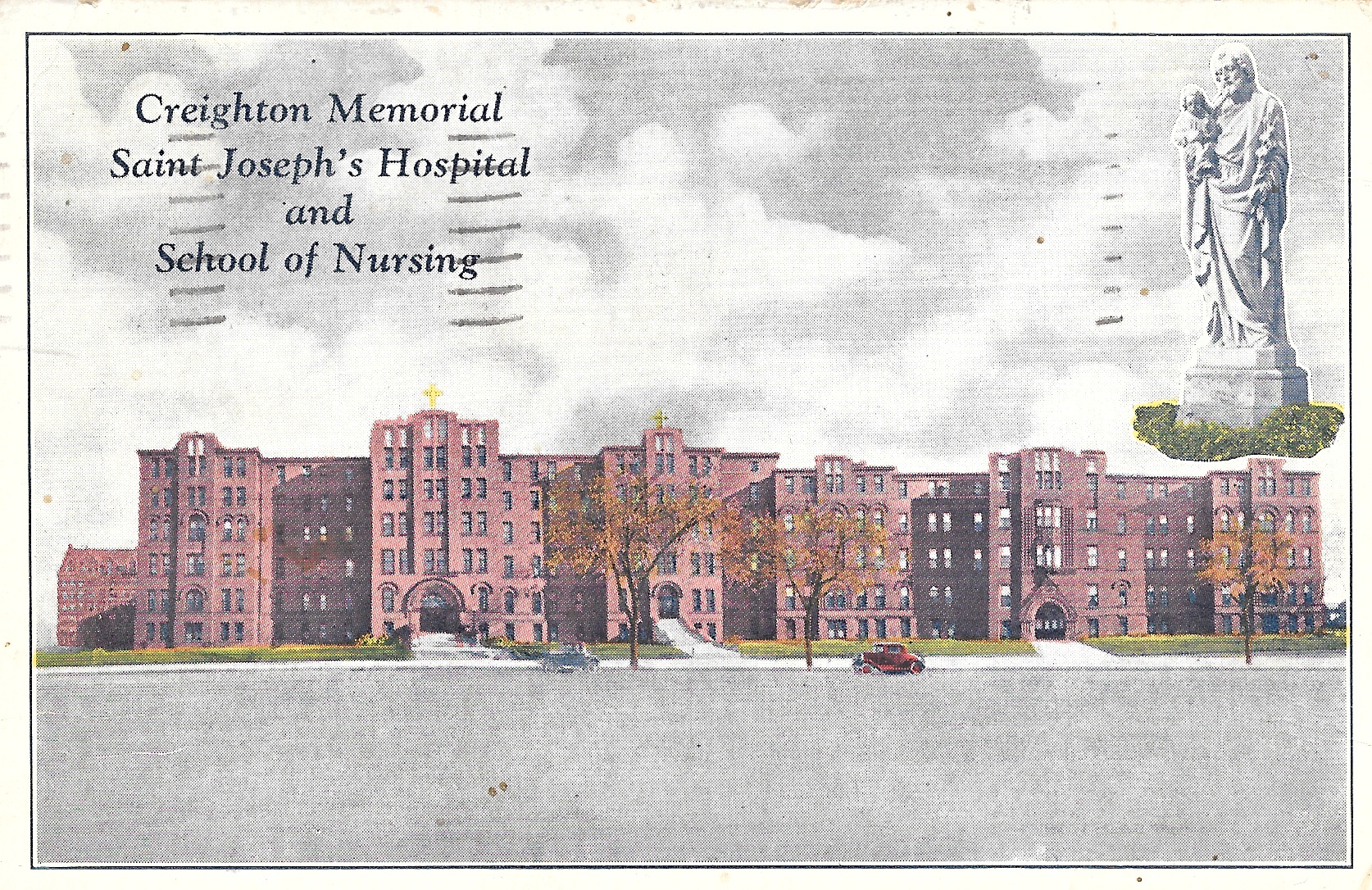

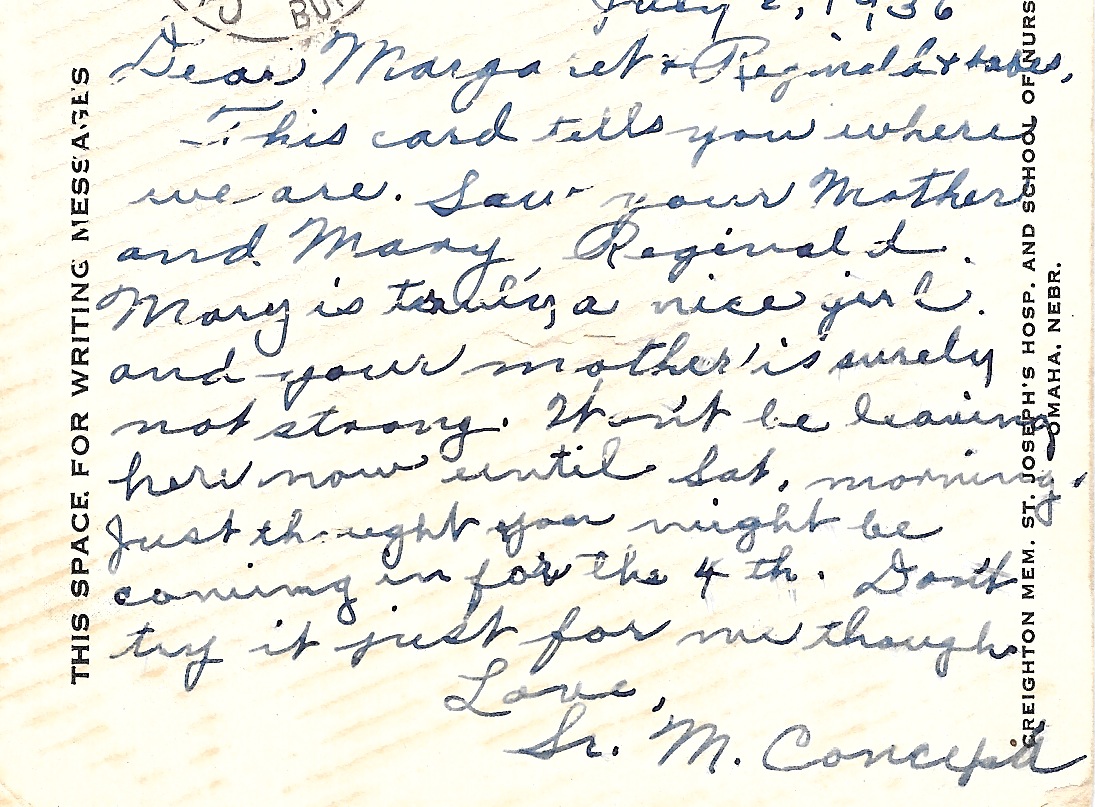

The USGS gives coordinates for Carlisle on its  “This card tells you where we are. Saw your Mother and Mary, Reginald. Mary is truly a nice girl and your mother surely is not strong. Won’t be leaving here now until Sat. morning. Just thought you might be coming in for the 4th. Don’t try it just for me though. Love, Sr. M. Concepta.”

“This card tells you where we are. Saw your Mother and Mary, Reginald. Mary is truly a nice girl and your mother surely is not strong. Won’t be leaving here now until Sat. morning. Just thought you might be coming in for the 4th. Don’t try it just for me though. Love, Sr. M. Concepta.”