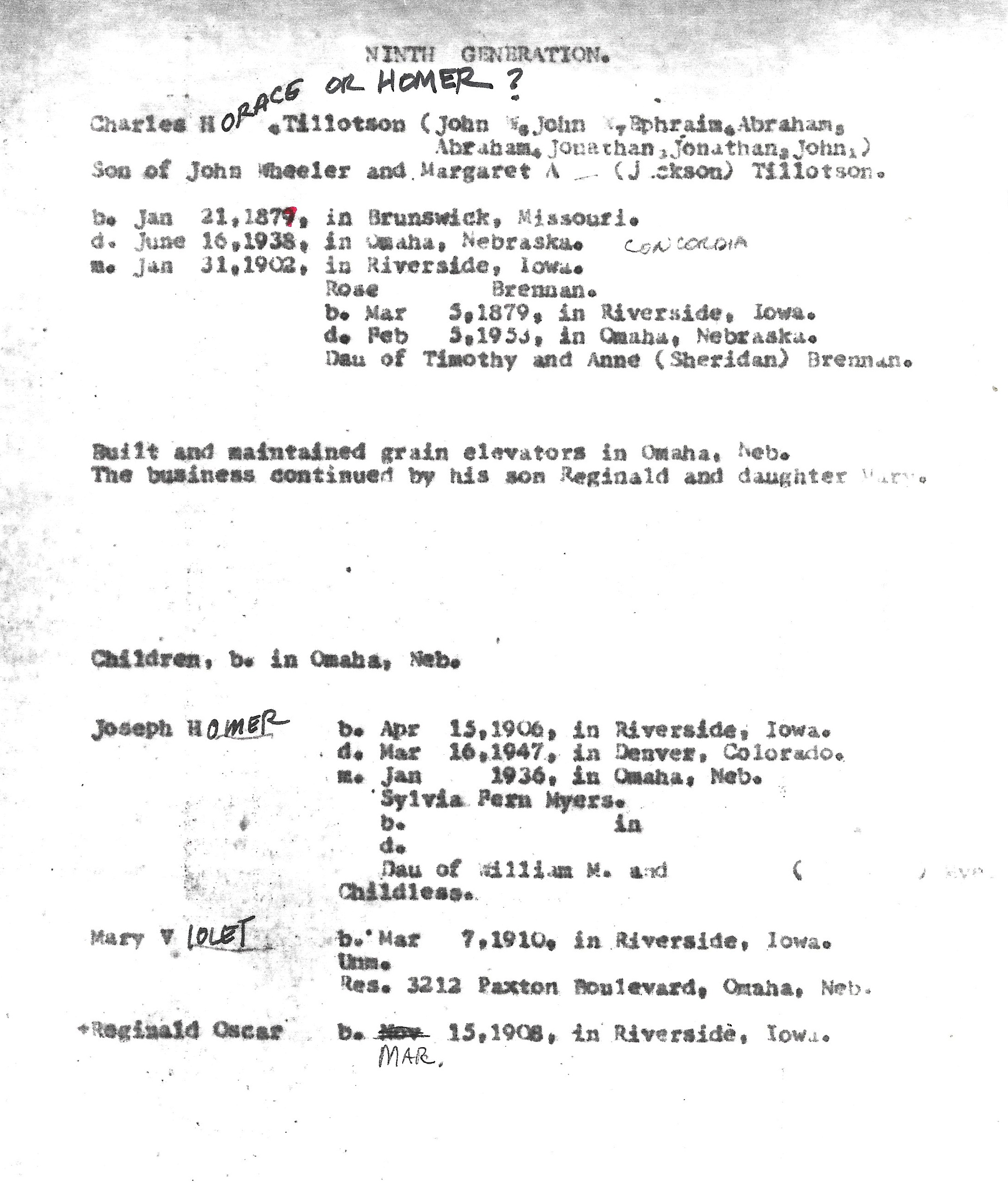

Grain Building Is the Work Of Omaha Firm

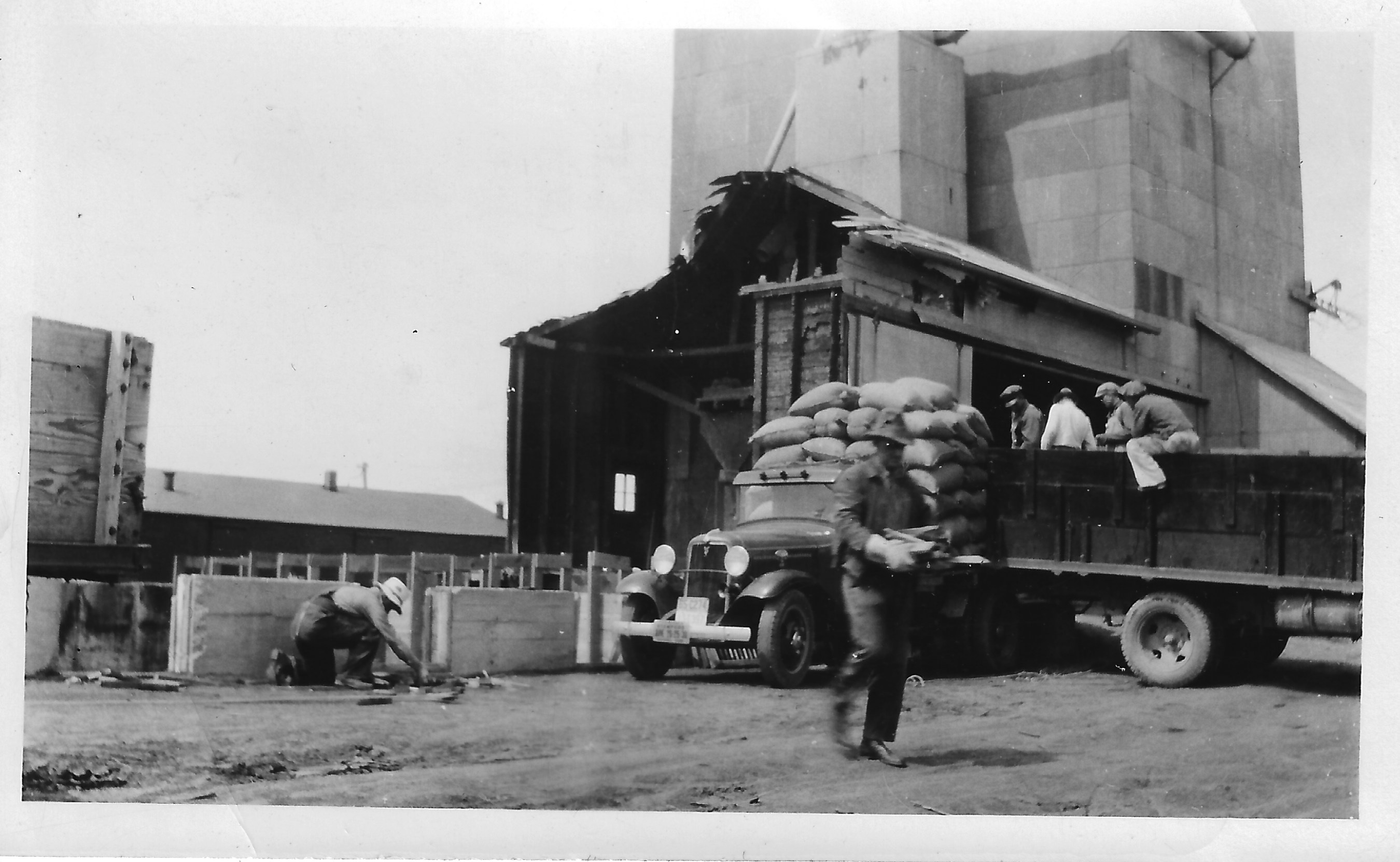

One of the largest wheat crops ever yielded by this section of the northwestern Oklahoma wheat belt was dumped into Goltry’s new 60,000 bushel elevator built for the Farmers’ Exchange of Goltry by the Tillotson construction company of Omaha, Nebraska,

The construction company operated by R.O and J.H. Tillotson, brothers, designers of modern concrete buildings, both of whom were in Goltry at various times during the progress of the building, was awarded the contract March 15. Shortly afterwards a crew of local workers began digging the pit, the first step in the actual construction of the new building.

Wheat was being dumped into the elevator at a time when the harvesting of wheat in this section was only beginning while electricians and skilled workers for the construction company were giving the building its finishing touches.

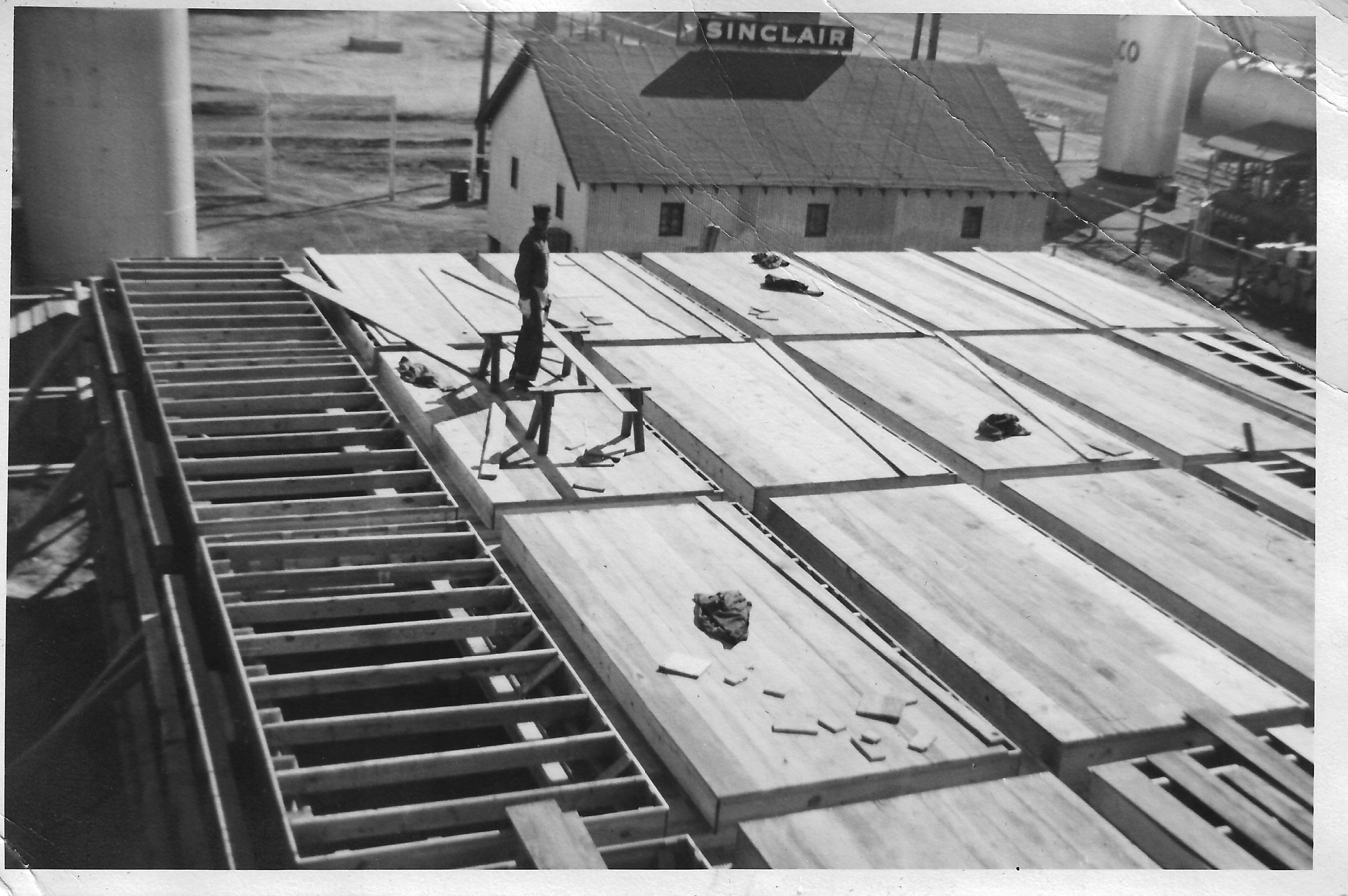

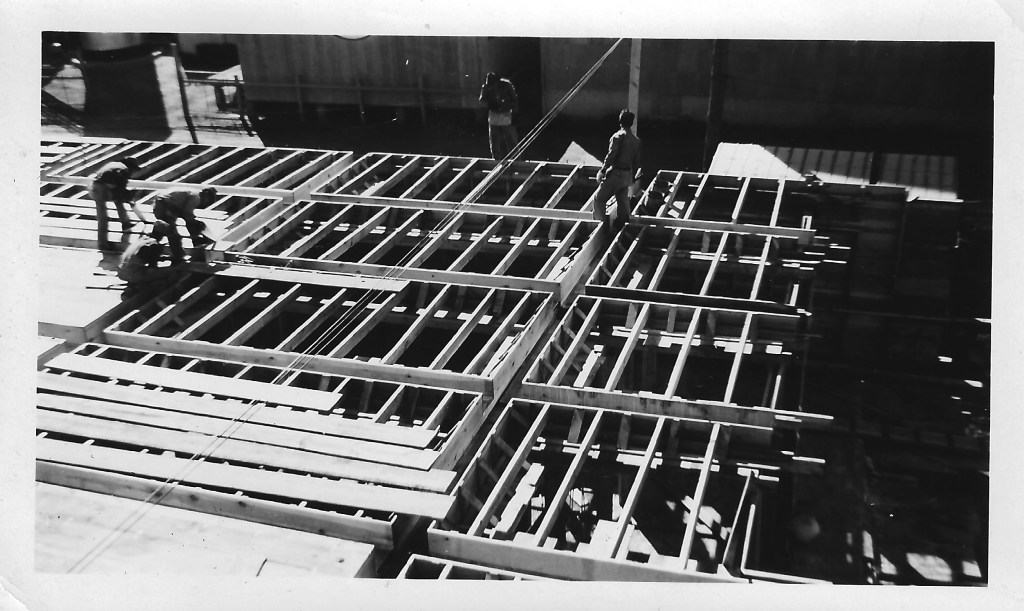

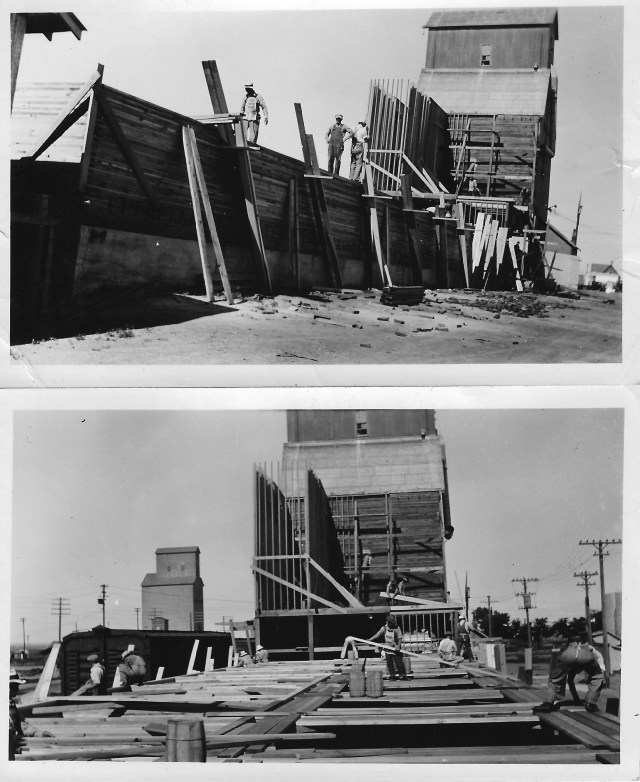

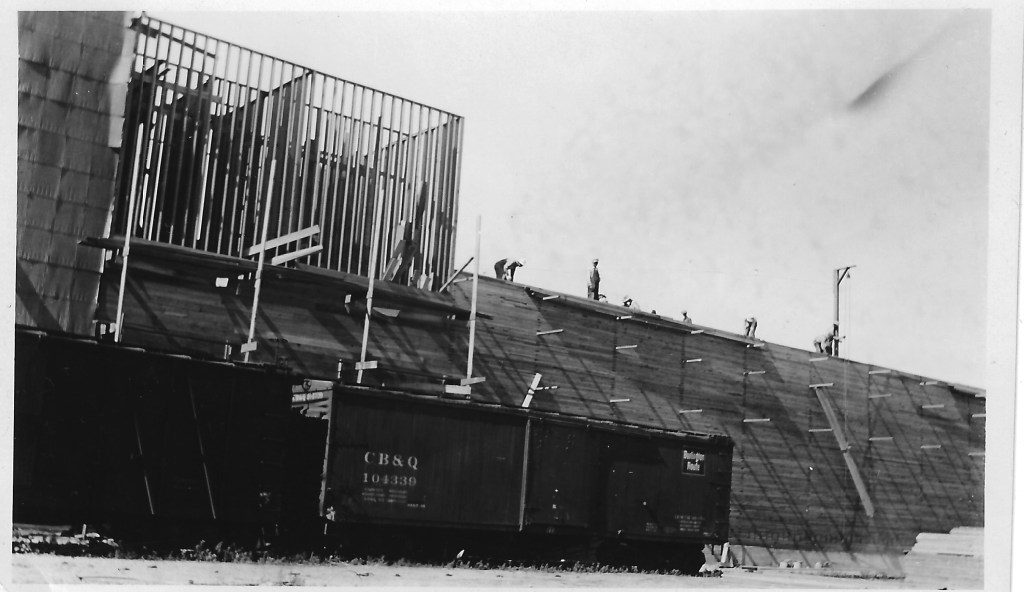

After the pit had been dug, a crew of 45 men–part of them local persons–was put to work by the company. Carpenters were building slip forms into which concrete was poured. The forms were four feet in height. As concrete was poured, the forms were moved upwards.

The forms were raised with jacks of which there were 48. All 48 jacks were turned by four men. Two turns of the jack screw raised the forms an inch and the jacks were turned in almost continuous operation.

The level of the forms was checked every hour in an effort to insure absolute accuracy. The Tillotson construction company used a new style of checking device in their job here. The company already had used five different kinds of checking devices during its various construction jobs. Employees of the company reported that the new device was the most accurate they had yet used.

The forms were raised an average of six feet every 10 hours. In the new checking device, targets were used in measuring distances with plumbs to keep the forms absolutely level all the way around at all times during their progress upwards.

The new style of checking system was not designed and made available until a short time previous to the date upon which the company began the Goltry job.

Before superintendent W.B. Morris, whose home is in Kansas City, left the job, 150,000 bushels of wheat had been put through the elevator. More than 85 carloads had been loaded from the elevator before Morris left. Each carload amounts to an average of 1,800 bushels. The machinery and equipment in the elevator were operating perfectly before the last of the company’s workers and the superintendent left the job.

“Everything ran smoothly with never a touch of trouble,” Morris, superintendent of the Goltry job for the Tillotson construction company, said.

A large amount of the responsibility for seeing that the day by day progress of the building was not interrupted at any time was delegated to Morris. However, Morris gave a great deal of the credit to the entire group of workers which included a number of local men. Morris said his company had “the best cooperation among the men working for us. We appreciate the interest shown by the people of the community and the efforts the men put forth endeavoring to keep the job going at the proper speed at all times,” Morris said.

The new elevator is 120 feet from the bottom of the basement to the top. The basement is four feet below the ground level and seven and a half feet below the floor. The capacity is 60,000 bushels.

A truck lift on the first floor of the elevator picks up trucks with ease in the process of dumping grain from the trucks into the pits. The new style of truck lift will not catch the radiator or damage the truck in any way.

A truck lift on the first floor of the elevator picks up trucks with ease in the process of dumping grain from the trucks into the pits. The new style of truck lift will not catch the radiator or damage the truck in any way.

Two pits into which grain is dumped hold 1,200 bushels. The first pit holds 850, the second 450.

Legs motivate the belt and cups and such a speed that the grain is elevated upwards into the bins at a rate of 60 bushels per minute.

At the top of the building, an automatic scale dumps 60 bushels per minute. The scale hold 10 bushels and automatically drops six times per minute.

A blowing system cleans wheat and sends the dust and chaff and foreign particles down a chute and into a compartment just above the first floor. At intervals this compartment is dumped into a truck and hauled away.

A fast cage type man lift–one of the fastest man lifts to be found in an elevator of the size of the new Goltry building–hoists the workers upward to the top of the building at a time saving rate of speed.

Among the various types of men working on the job–of which there were as many as 45 at the time the crew was running slip forms–were electricians, concrete workers, steel men, jack men, hoisting engineer, concrete mixer operator, finishers who smoothed the walls and the floors, painters, buggy men and wheel barrow men.

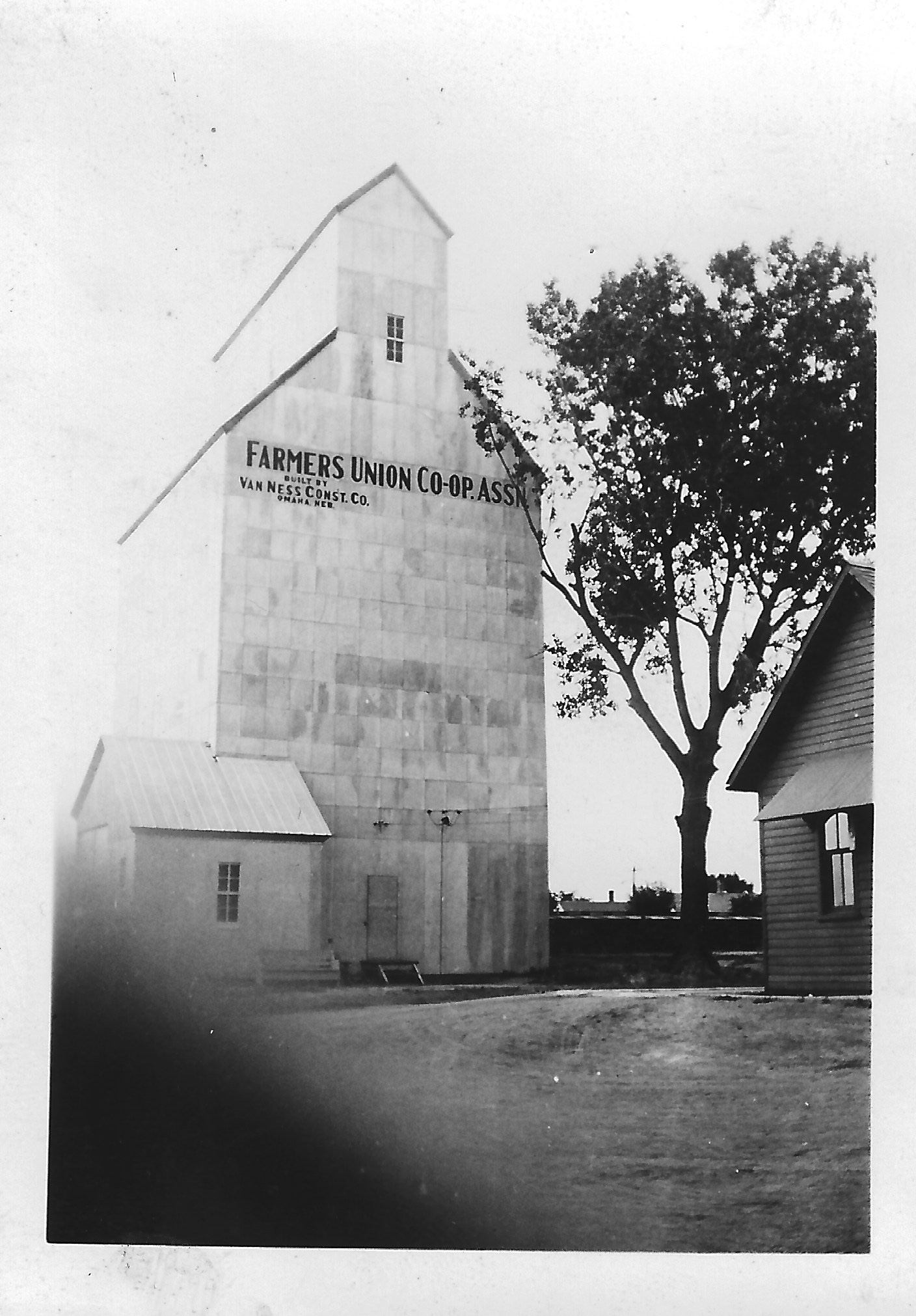

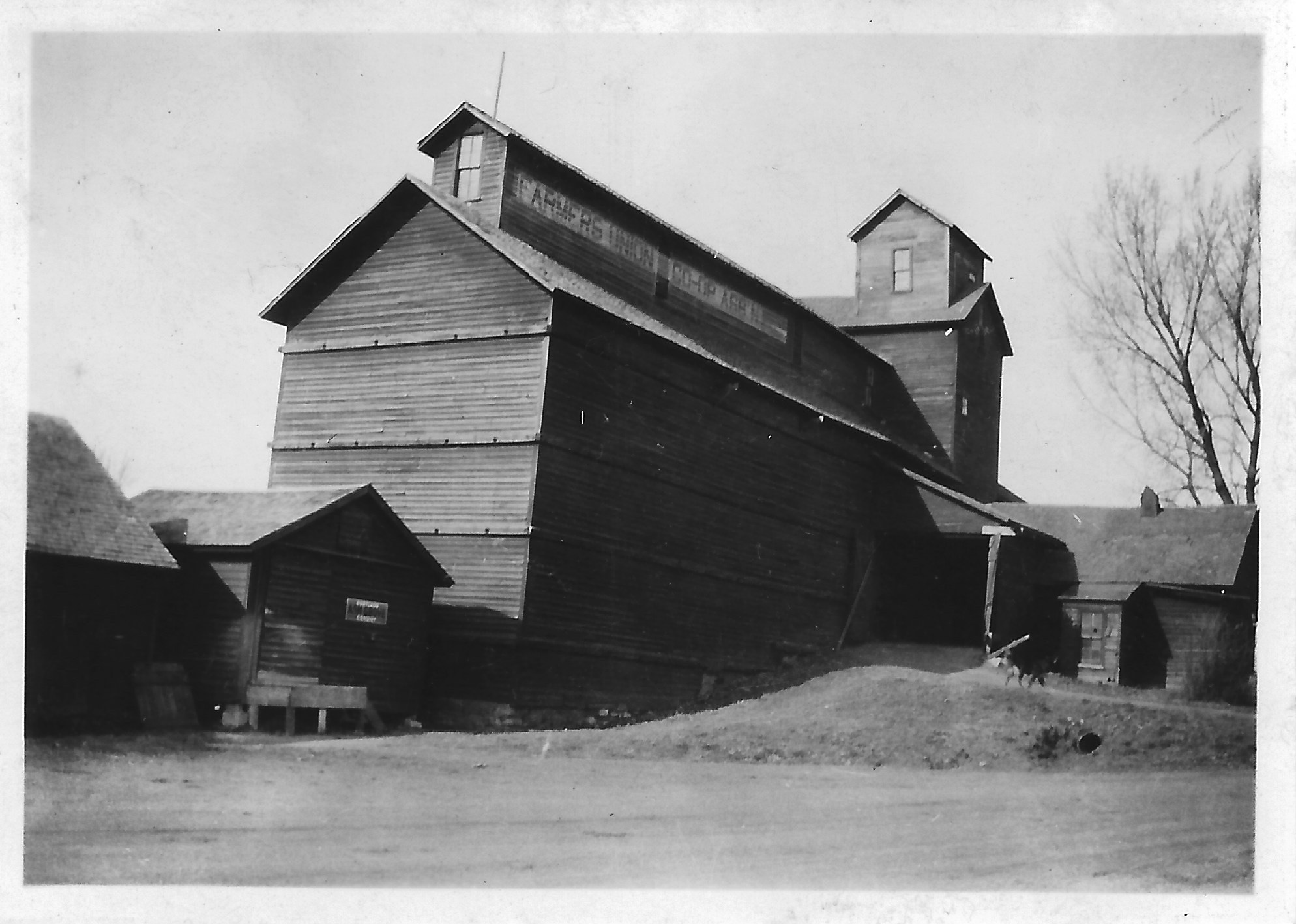

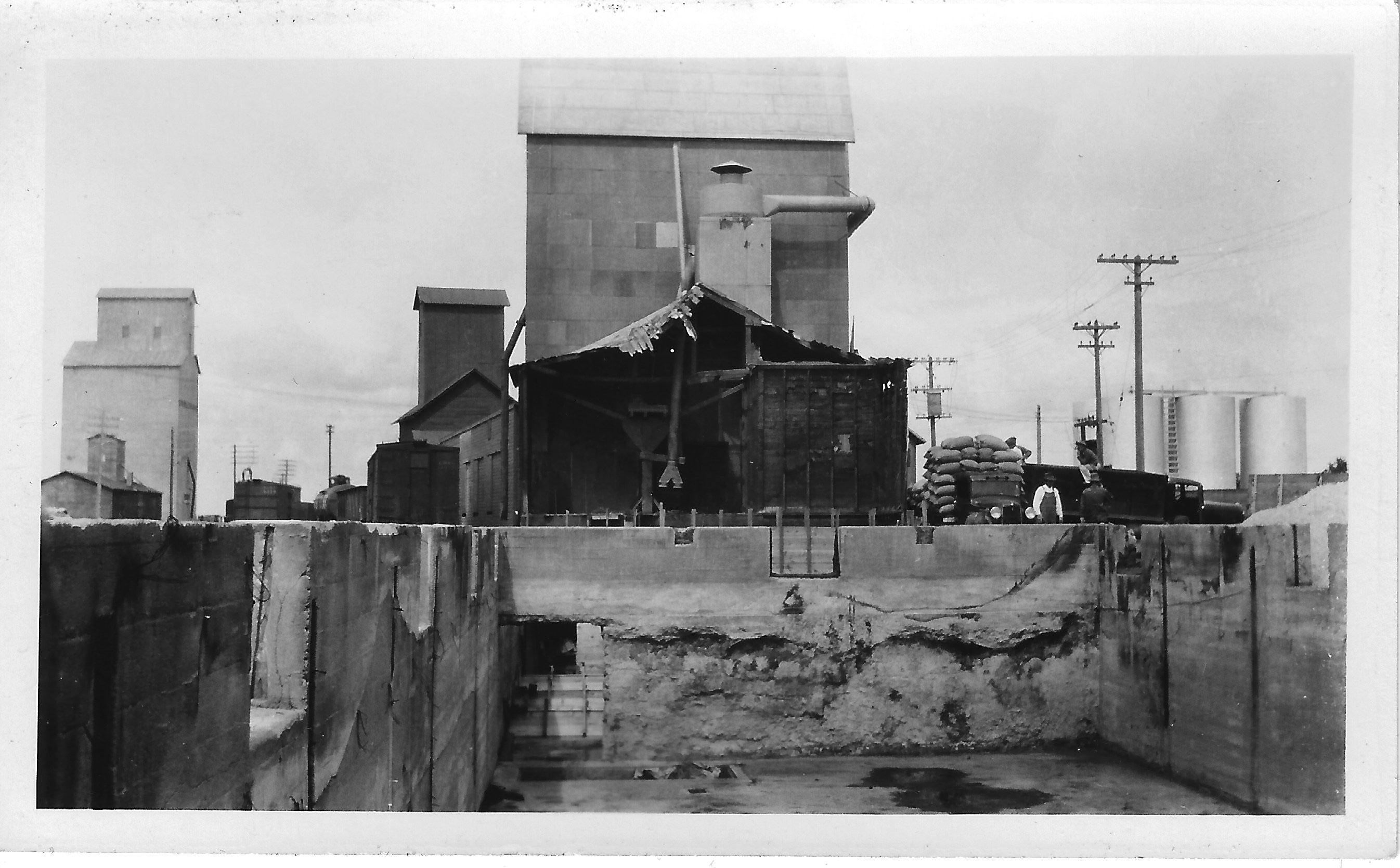

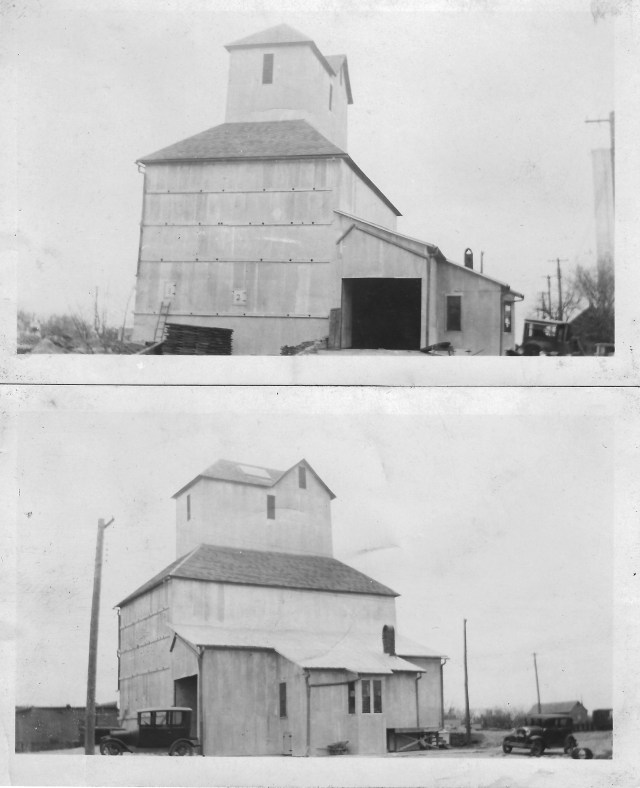

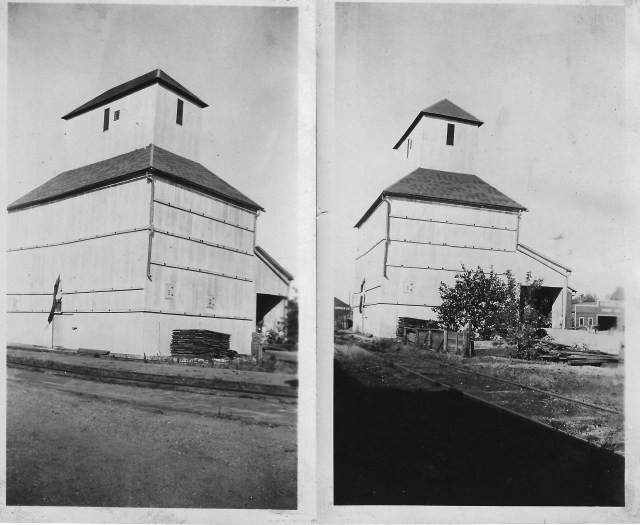

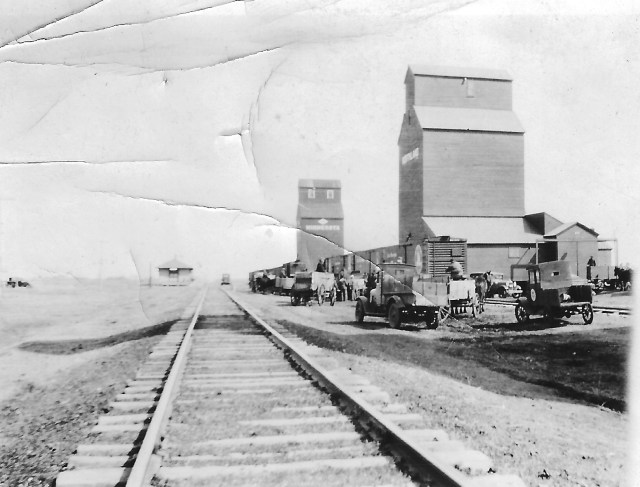

Front page caption:

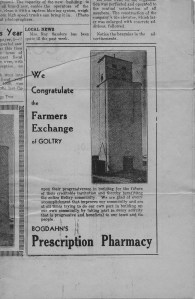

Goltry’s new modern elevator building (above), built for the Farmers’ Exchange of Goltry by the Tillotson construction company of Omaha, Nebraska, is 120 feet in height, rising 116 feet above the ground level and falling four feet below the level of the ground. The capacity of the new building is 60,000 bushels and its modern machinery and equipment, all brand new, enable the operators of the Farmers’ Exchange to dump grain into the pit, elevate it, clean it with a modern blowing system, weigh it and load it into waiting box cars as rapidly as modern high speed trucks can bring it in. Photo exclusively for The Goltry Leader by Cochrane commercial photographers.

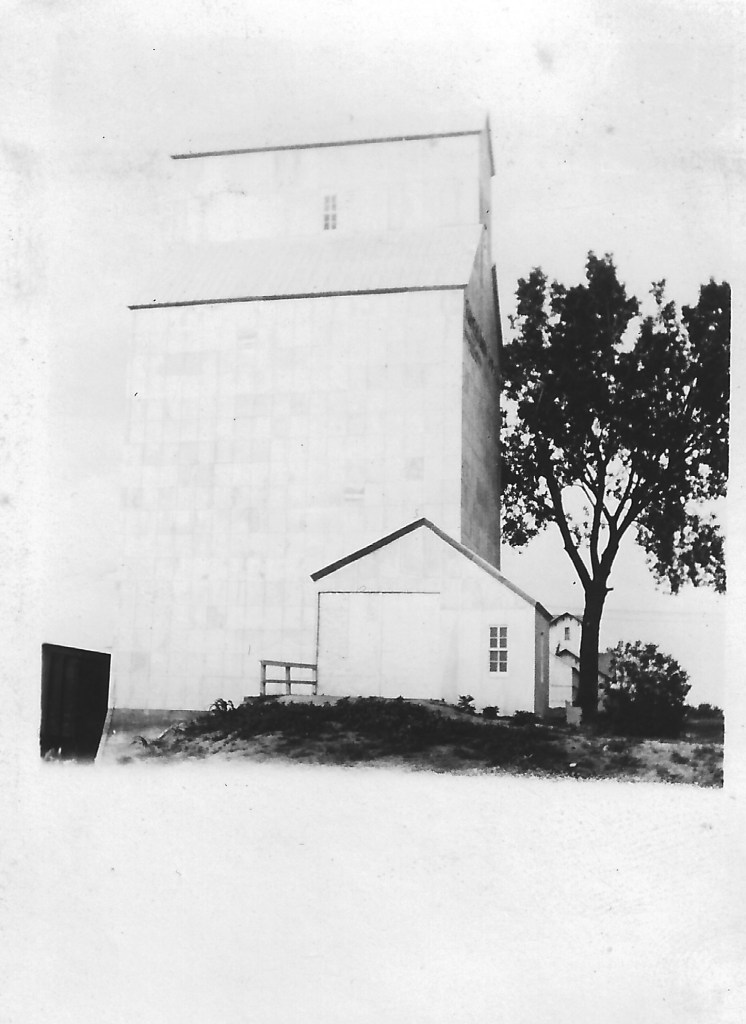

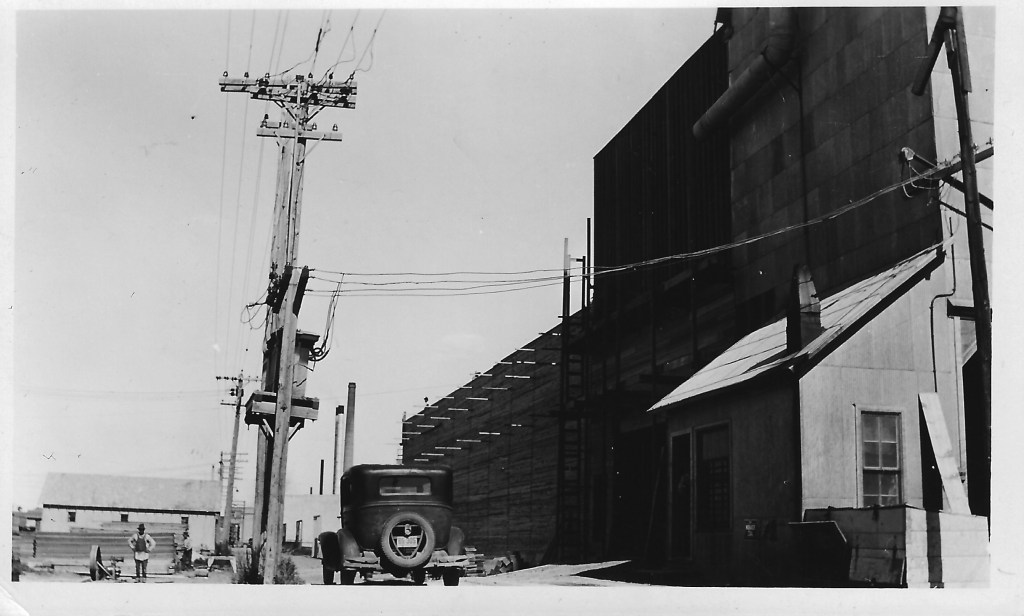

Inside page caption:

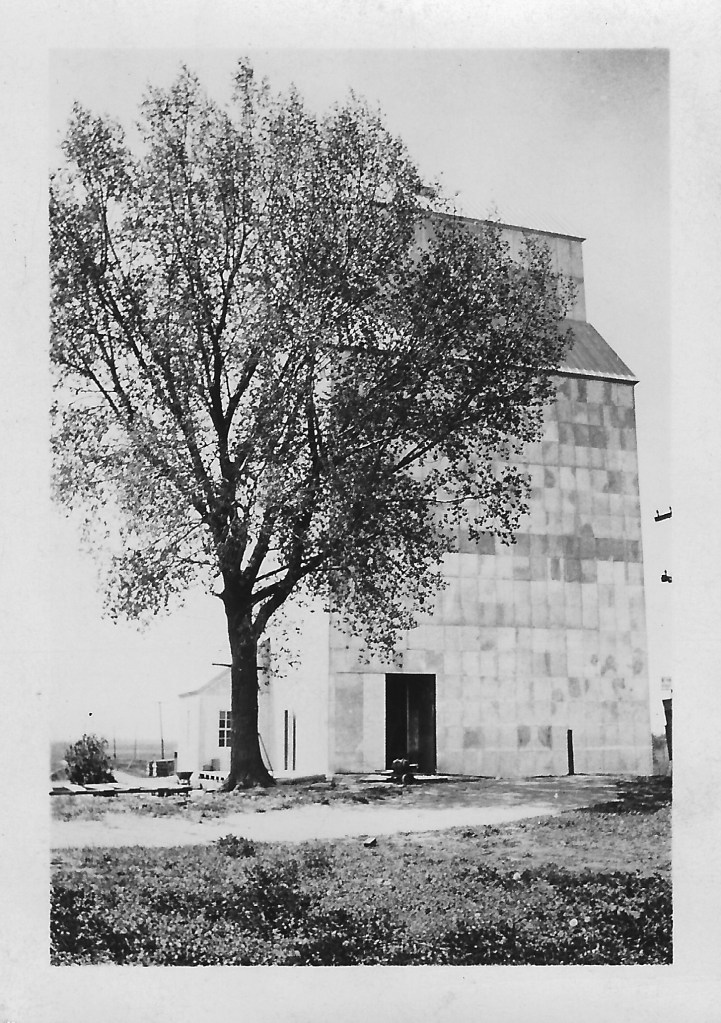

Approaching Goltry from the west a person would be afforded this view of the new Farmers’ Exchange elevator building (above) towering 116 feet toward the sky, its smooth, white walls reflecting with added brilliance the dazzling rays of the midsummer, afternoon sun. (Photo exclusively for The Goltry Leader by Cochrane commercial photographers).