By Ronald Ahrens

Tillotson Construction Co. built at a dozen and a half locations in Oklahoma, and I was now trying to see several of then in an afternoon before staying overnight in Enid.

After my impromptu visit to Shattuck, I drove east on U.S. 60 for another hour or so until I reached Orienta. The wind, which must have been blowing 40 mph, was behind me.

After my impromptu visit to Shattuck, I drove east on U.S. 60 for another hour or so until I reached Orienta. The wind, which must have been blowing 40 mph, was behind me.

Arriving at Orienta, I found an elevator complex at the highway junction with but very little in the way of a town. One of the steel buildings at the complex was labeled W.B. Johnston Grain Co.

In 2014, Johnston, which must have come after the Orienta Co-op Association, sold its 19 country grain elevators to CGB Enterprises, Inc. I had just come from CGB’s location in Shattuck.

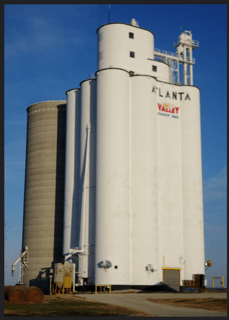

The south elevator and Tillotson’s storage annex at Orienta, Okla.

Orienta optimistically took its name from the Kansas City, Mexico, and Orient railway, which was called The Orient railroad.

I knew Tillotson had built here in 1954 but was disappointed to find it was only a storage annex. (As usual, I hadn’t studied the construction record too thoroughly beforehand.)

There were two elevators, each with an annex.

The south elevator was put up by Johnson Elevator Construction Co. This house is about as unprepossessing as they come: silos compressed in a small area and a pretty average-looking rectangular headhouse.

Tillotson’s manhole cover.

Attached to it is Tillotson’s annex of 10 tanks, or silos, of 20 feet in diameter. They are 114 feet 9 inches tall. Capacity was 312,000 bushels.

I had to accustom myself to the notion that Tillotson would build storage silos alone. After all of our grand talk about curved headhouses and a singular style, this job was generic. There’s no glory in annexes, but there was money.

And I find that Tillotson built eight storage annexes in 1954. They were in Iowa, Kansas, Texas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. Company records for that year list 16 jobs in all, so storage was half of the business.

The annex is holding up much better than the main house. Johnson used a coarse aggregate for its concrete, which is crumbling in some key places. It would be interesting to know when this job was done and the circumstances behind it.

The north elevator has an elegant stepped headhouse with plenty of curves. Some faded lettering can still be read: “Orienta Co-op Ass’n.” (For grammarians among us, that’s nice use of the apostrophe to represent missing letters!) I found Johnson-Sampson on the manhole cover. Kristen and I believe that design philosophy trickled down to this company from Mayer-Osborn.

On the south face of the crumbling Johnson elevator, visible above the Tillotson annex, the same slogan appears in a burnt sienna color.

I’m seeking more information about this complex and will provide an update when more news is revealed.