By Ronald Ahrens

At 320,000 bushels, Bellwood, Neb., and Canyon, Tex. were the second-biggest jobs for Tillotson Construction Co. when they were built in 1950, some 12 years after the company’s first elevator of reinforced concrete.

There was the early, huge 350,000-bushel facility at Farnsworth, Tex., in 1945.

There was the early, huge 350,000-bushel facility at Farnsworth, Tex., in 1945.

Otherwise, the 310,000-bushel elevator at Dalhart, Tex., in 1949, was next-largest.

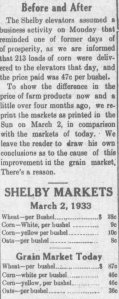

We now find this welcome history of the Bellwood elevator complex–which presents slightly different figures from those in the company record–from a local source:

The first concrete elevator was built in 1950 with a capacity of 324,000 bushels and a cost of $141,000. The first addition followed in 1954 costing $133,000 and holding 344,000 bushels. The second annex of 343,000 bushels followed in 1958 with a price tag of $116,000. The third annex, being the north elevator with the headhouse, was built the next year for $179,000 and has a capacity of 290,000 bushels. Twenty years later, in 1979, two large diameter tanks each holding 165,000 bushels, were built at a total cost of $333,000. This brings the companies (sic) licensed storage capacity to 1,685,000 bushels.

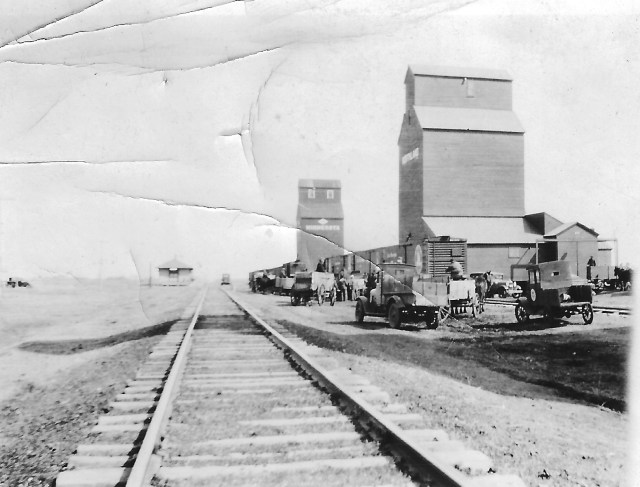

As reported in the previous post, we found the Frontier Cooperative location to be surviving quite nicely after 70 years and two explosions.

Here is this detail of the first one:

An explosion ripped through the first concrete elevator on March 27, 1959 causing considerable damage to the basement and headhouse areas. Seriously injured in this explosion were Jim Mick and Walker Meyers, both employees of the Farmers Co-op Grain Co.

The original house was built with 2,436 cubic yards of reinforced concrete and 20.3 yards of plain concrete for the hoppers.

Reinforcing steel amounted to 143.3 tons, which worked out to 115.3 pounds per cubic yard.

The structure sits on a main slab of 66 x 77.5 feet. We work that out to 5,115 square feet, but the construction details in the company records note, “Act. Outside on Ground” and give the figure of 4,806 square feet.

The reinforced concrete and steel weighed in at 5,069 tons, and the tanks could accommodate 9,600 tons of grain. Incorporating other factors like 28 tons of structural steel and machinery, as well as 40.3 tons of concrete for the hoppers, the gross weight loaded was an impressive 14,964 tons.

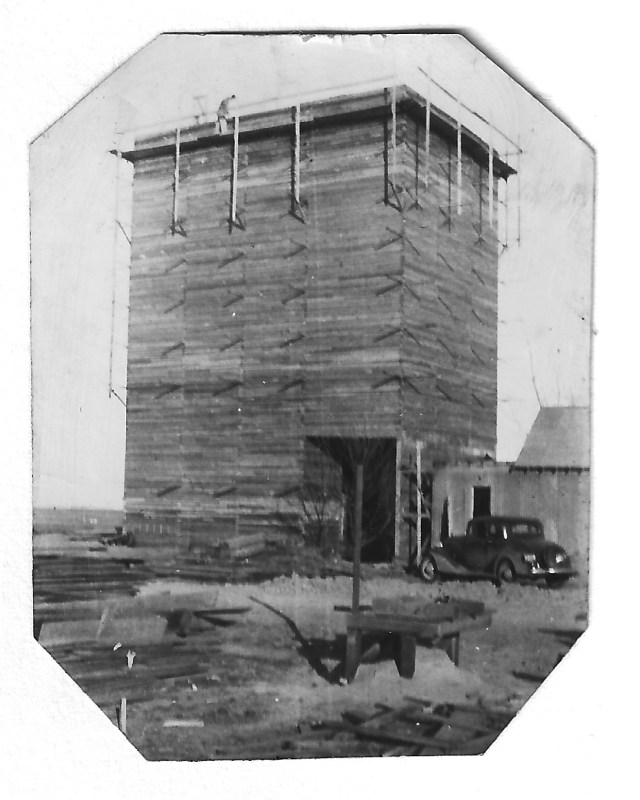

All this massiveness was quite a testament of progress. We have to remember that just 12 years before–with the period of inactivity during World War Two intervening–the Tillotsons were building cribbed wooden elevators.

The main slab covers a pit of 15 feet 9 inches deep.

Way above the pit, the cupola (headhouse) was quite a specimen at 23 feet wide, 63.75 feet long, and 39 feet high–identical to Canyon and pretty comparable to the 300,000-bushel elevators that were also built in 1950 at Burlington, Colo., and Hartley, Texas. All of these elevators were built on the same plan that was original to Bellwood, yet the tanks at Burlington and Hartley rose to 115 feet instead of 120 feet and the cupolas were five feet taller than those at Bellwood and Canyon.

Way above the pit, the cupola (headhouse) was quite a specimen at 23 feet wide, 63.75 feet long, and 39 feet high–identical to Canyon and pretty comparable to the 300,000-bushel elevators that were also built in 1950 at Burlington, Colo., and Hartley, Texas. All of these elevators were built on the same plan that was original to Bellwood, yet the tanks at Burlington and Hartley rose to 115 feet instead of 120 feet and the cupolas were five feet taller than those at Bellwood and Canyon.

The single-leg Bellwood house boasted 72-inch-diameter head and boot pulleys that were 166 feet apart; the 14-inch, six-ply Calumet belt stretched an impressive 360 feet. The record shows that the belt’s cups, of 12 x 6 inches, were spaced 8.5 inches “o.c.”

Powered by a 40-horsepower Howell drive, the head pulley could turn a 42 rpm. It provided a theoretical leg capacity of 7,920 bushels per hour. Actual leg capacity at 80 percent of theoretical used 32 horsepower for 6,350 bushels per hour.

The 1981 explosion destroyed the cupola and, we presume, all its contents. We hope to find period photos of before and after.

Records show the 1954 annex with capacity of 340,000 bushels. It consumed 2,129 cubic yards of reinforced concrete and 119.5 tons of steel.

Records show the 1954 annex with capacity of 340,000 bushels. It consumed 2,129 cubic yards of reinforced concrete and 119.5 tons of steel.

The 24-inch-thick slab–same thickness as at the main house–spread over 45.5 x 107 feet for “Act. Outside on Gd.” of 4,569 square feet.

The 10 tanks of 20 feet in diameter reaching 130 feet high required 4,377.5 tons of reinforced concrete and yielded a gross loaded weight (with 10,200 tons of grain) of 15,628.5 tons.

The cupola, or run, atop this annex was 13 feet wide, 100 feet long, and 8.4 feet high.

Top and bottom belts were 30 inches wide and moved at 600 feet per minute. A 10-horsepower drive at top and 7-horse drive at bottom enabled movement of 9,000 bushels per hour.

As we saw for ourselves, the second annex, a 1958 job, bears manhole covers embossed with the Tillotson Construction Co. stamp. Alas, our records stop at 1955.

Nevertheless, we expected to see an elevator with a replacement structure at its crown.

Nevertheless, we expected to see an elevator with a replacement structure at its crown.