Preston conflagration photos from 2012 courtesy of Ryan Day.

By Ronald Ahrens

In Franklin County, Idaho, the towns of Downey and Preston are about 30 miles apart on U.S. 91. Downey is small, Preston is large. More than 5,000 people live in Preston. It’s the county seat.

As Ryan Day expresses it, “Downey is the black sheep of the family nobody wants to talk about.”

Ryan, a follower of Our Grandfather’s Grain Elevators, runs the historic mill and elevator complex in Downey, which is a unit of Valley Wide Cooperative. Competing against the operation in Preston was tough. Preston had 24- and 36-inch rollers for barley, and a board member claimed no one could roll barley as well as they did. Preston flaked corn with the same proficiency that Sammy Cahn churned out timeless romantic songs. Preston could even apply molasses to the feed it produced.

This mill in the metropolis was fancy-schmancy.

“They were always the enemy,” Ryan says.

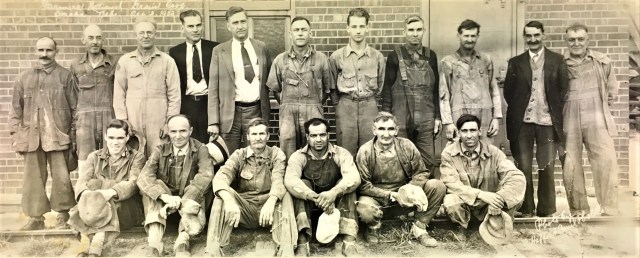

Jene Day, who operated Downey for about 50 years, finally lured his son back in 2012 to become his successor. A month before Ryan’s first day on the job, the big mill in Preston caught fire and burned down.

“When I started, the building was still smoking,” he says.

The black cloud that had billowed over Preston had a silver lining, though.

“They had just merged with Valley Wide. Luckily, they were insured and able to build a new state-of-the-art mill.”

In 2014 The Capital Press–“The West’s Ag Weekly Since 1928”–celebrated the reconstituted mill’s opening and extolled its efficiency and convenience. The $3-million facility had everything producers and feeders could want: exotic mixes and the quick loading and unloading of trucks, for example.

Such a powerful allure caused a crisis of faith with some of the organic dairymen who had depended on Downey.

According to the the Capital Press, “Mike Geddes a local organic dairy owner [sic], said about a dozen regional organic dairies who now use a dilapidated mill in Downey have asked Valley Wide to process their feed.”

Dilapidated? A black eye for the black sheep!

Preston may be more efficient, but it’s just another unprepossessing steel building with some small steel bins. It lacks any visual distinction whatsoever. In fact, in the photos we’ve seen, it’s darn near invisible.

Kristen Cart’s photo captures Downey’s Oz-like quality. L. Frank Baum’s Oz books were contemporaneous with much of Downey’s construction.

As stated in an earlier post, Downey’s buildings belong to Oz. The installation should be in our National Register of Historic Places. For that matter it should be registered in Oz, too.

Four years have passed since Preston re-opened. To find out if anything has been done about its going organic, I called up and spoke to feed manager Shaun Parkinson.

“The only reason that we’d do anything is if something happened to Downey,” he said.

In other words Downey has its niche and is in good hands with Ryan Day.

Nothing had better happen.

“They cornered three fellows and a gal from Chicago going through the states doing a robbery spree,” Ryan said.

“They cornered three fellows and a gal from Chicago going through the states doing a robbery spree,” Ryan said.

For said reason we present Kristen’s photos of a venerable operation in Downey, Idaho. This is one-of-a-kind hybrid complex of metal-clad wooden buildings and gleaming steel silos. A conspicuous ovalized Oz-like headhouse is freakish-tall but not inelegant.

For said reason we present Kristen’s photos of a venerable operation in Downey, Idaho. This is one-of-a-kind hybrid complex of metal-clad wooden buildings and gleaming steel silos. A conspicuous ovalized Oz-like headhouse is freakish-tall but not inelegant.

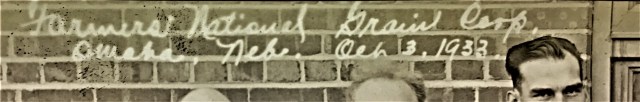

I had only been to the Mayer-Osborn elevator in Tempe, Ariz., and Tillotson Construction Co.’s 1947 terminal in my hometown of Omaha. (Also, a superficial look-see at an elevator-mill complex in Colton, Calif., about an hour from my house.)

I had only been to the Mayer-Osborn elevator in Tempe, Ariz., and Tillotson Construction Co.’s 1947 terminal in my hometown of Omaha. (Also, a superficial look-see at an elevator-mill complex in Colton, Calif., about an hour from my house.)