By R. Janet Walraven

As a child growing up in the slip-form concrete industry, I probably never heard of most of the challenges my parents faced. But I do remember some.

My mother, Sadina, was intrigued by slip-form construction, as I have been all my life. There is something special about revisiting what I call prairie skyscrapers across the Great Plains.

Being a superintendent, Daddy usually went ahead in his pickup to start a job. Mama would follow with my two sisters and me, stair-stepped closely in age, with everything we owned in the trunk of the car. Finding a place to live was challenging; many times, she would be turned away because owners did not want to rent to “construction rats.” Most of the time the apartment or house she found was old, small, and sometimes not very nicely kept. Mama would have the place spic-and-span by the time Daddy got home for supper. Her motto: “Always leave it better than you found it.”

As time went on, Daddy collected a group of loyal foremen–carpenters, steelworkers, electricians, and laborers–whose wives and families followed wherever the job took us. Many chose to live in trailer houses pulled by their pickups. Daddy refused to live in a trailer house.

Mama was the best teammate Daddy could have found. She cooked, baked, and cleaned, and she sewed all the clothes for us girls and herself. She planted a garden if we would be in one place long enough. She washed, starched, and ironed to perfection with only a wringer-washer most of the years. And she served as Bill’s payroll bookkeeper. In addition, she planned social gatherings for the crew: picnics, baseball games, birthdays, and roller-skating parties. She knew it was important to keep the crew together. Daddy and Mama made lifelong friends, even after some of them drifted off when their wives and children no longer wanted to keep moving around.

While in Albuquerque in 1958 to 1960, Daddy purchased the 38-unit Texas Ann Motel on Route 66. Mama operated it for two years. When his next job required another move, she found managers and was thrilled to be back on the road experiencing new adventures.

‘Safety first’ in a hazardous undertaking

One of Daddy’s priorities was safety first. Working on a slip-form concrete job was very dangerous. He paid attention by always being where the action was and insisted on everyone keeping the jobsite orderly. In all of his dozens of jobs, I remember only two incidents where he lost a man. One was in Hereford, Tex., where a man fell to his death from the top of the elevator. Daddy was in deep grief; he felt responsible for the tragedy and took on the responsibility of caring for the bereaved family.

The second was in Plainview, Tex., where a subcontracted electrician, standing at the top of the elevator, accidentally stepped into his own toolbox and fell through a manhole.

While building, Daddy endured a few situations of his own. Once climbing the ladder up the side of an elevator, he fell and broke his leg. A week later, not being able to get around on the job well enough, he sawed off the cast and limped around until the leg was healed. He never lost one day of work in his entire career.

Unions can also be challenging. When the Teamsters went on strike, they were stopping the non-union cement truck drivers and pushing the trucks over into the ditch. The drivers then refused to continue. Daddy got into the driver’s seat of a truck, held a gun out the window, and drove across the strike line. No one messed with my dad, and the strike was over.

Another incident was when he had to fire a laborer. The next day, the man came onto the job, came up behind Daddy, and hit him in the head with the hammer claw. A foreman took the guy down, drove Daddy to the emergency room to get stitches, and they both went back to work. That same foreman who saved Daddy’s life was Will Evans, a black man whose family was very close to ours. I was riding with Daddy when we moved to Sunray, Tex. and was shocked to see a billboard at the city limits that read: “All Negroes must be out of town by sunset.”

“What does that mean?” I asked. “Where will Will and his family live?”

Daddy gritted his teeth and said, “I’ve bought him a trailer house to put out on the jobsite.”

It was my first encounter with prejudice. Daddy looked after that family until all their children were grown.

Excitement of ‘The Pour’ and pride in workmanship

I loved riding with Daddy to the next town. As soon as I could read, he taught me how to navigate by map, letting him know what the next highway route was, though he probably already knew. As we rode along, passing through small towns that had grain elevators built by someone else, he would say, “See the lines running horizontally in those tanks? That’s where the superintendent in charge kept pouring concrete even when the weather was below freezing. A freeze line is a weak place that can cause a blowout in the tanks. I will not let that happen.”

I had a great sense of pride in his perfectionism. He was also proud of grain elevators that had a headhouse and “Texas house” that contained the equipment: the uppermost leg and the “run” to the storage tanks. He said all other elevators were messy-looking because so many mechanisms were outside the structure. To this day, I can spot a Chalmers & Borton grain elevator miles away.

One of the most exciting times of my childhood was watching a week-long pour. Daddy stayed on the job night and day, coming home only to eat, bathe, and change clothes.

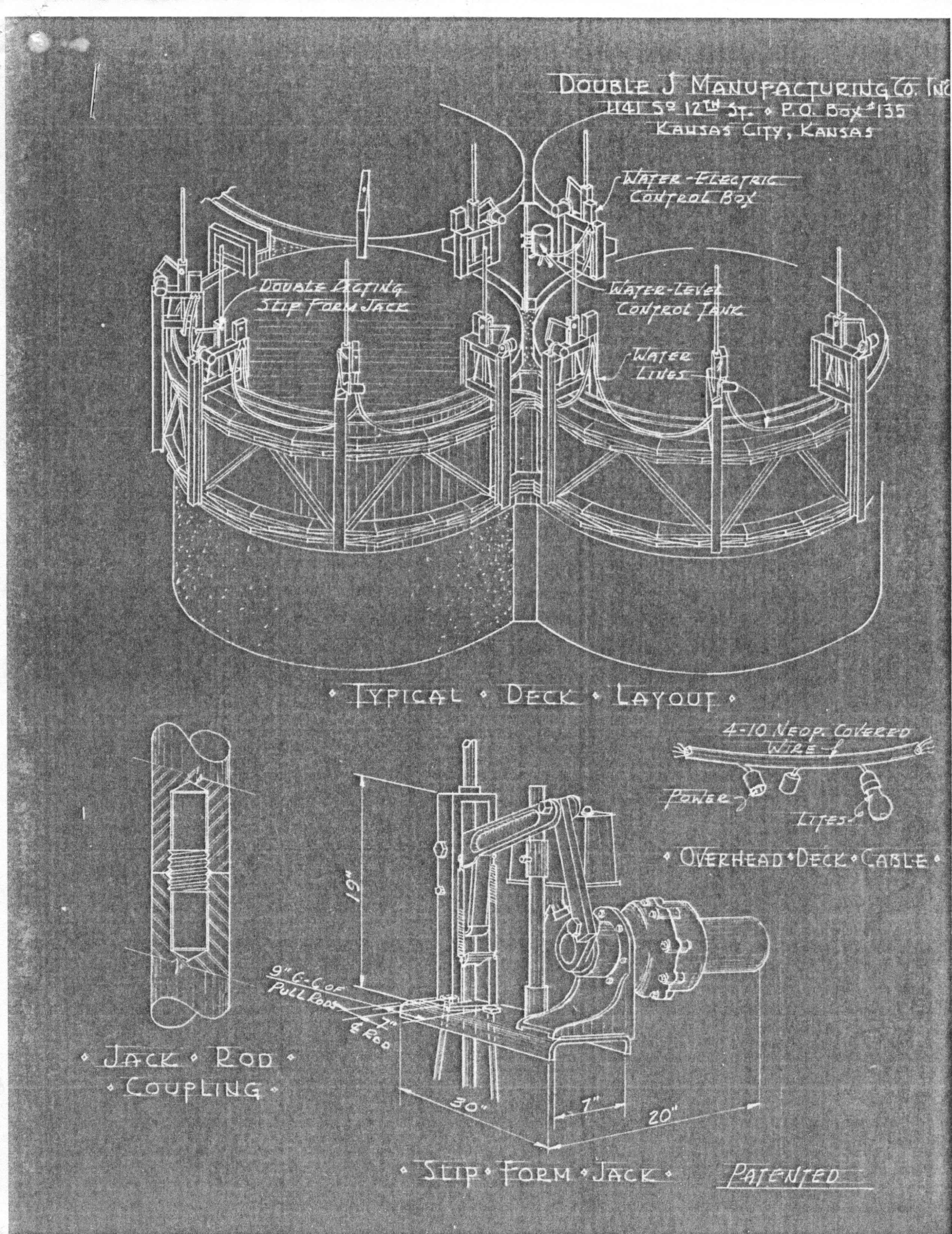

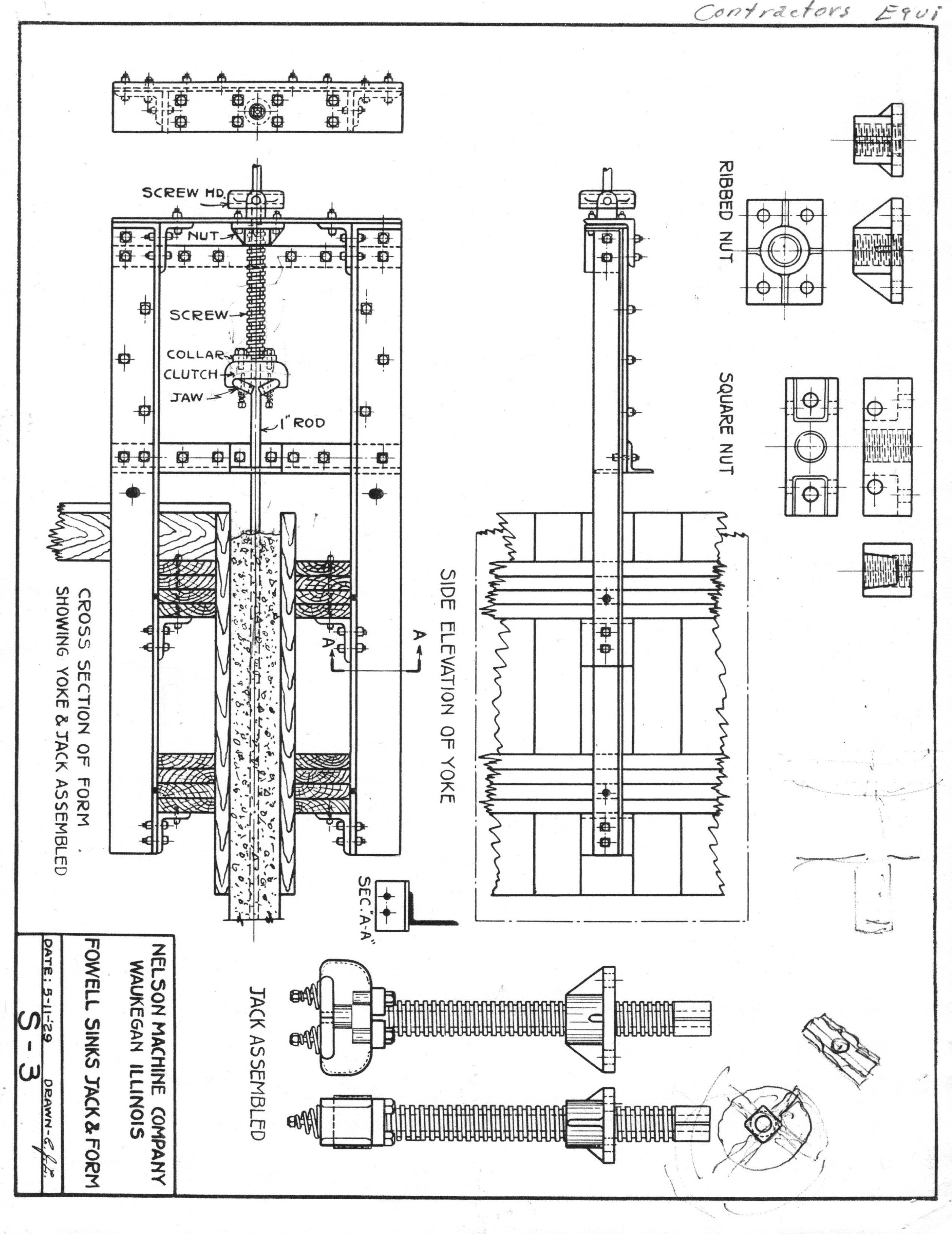

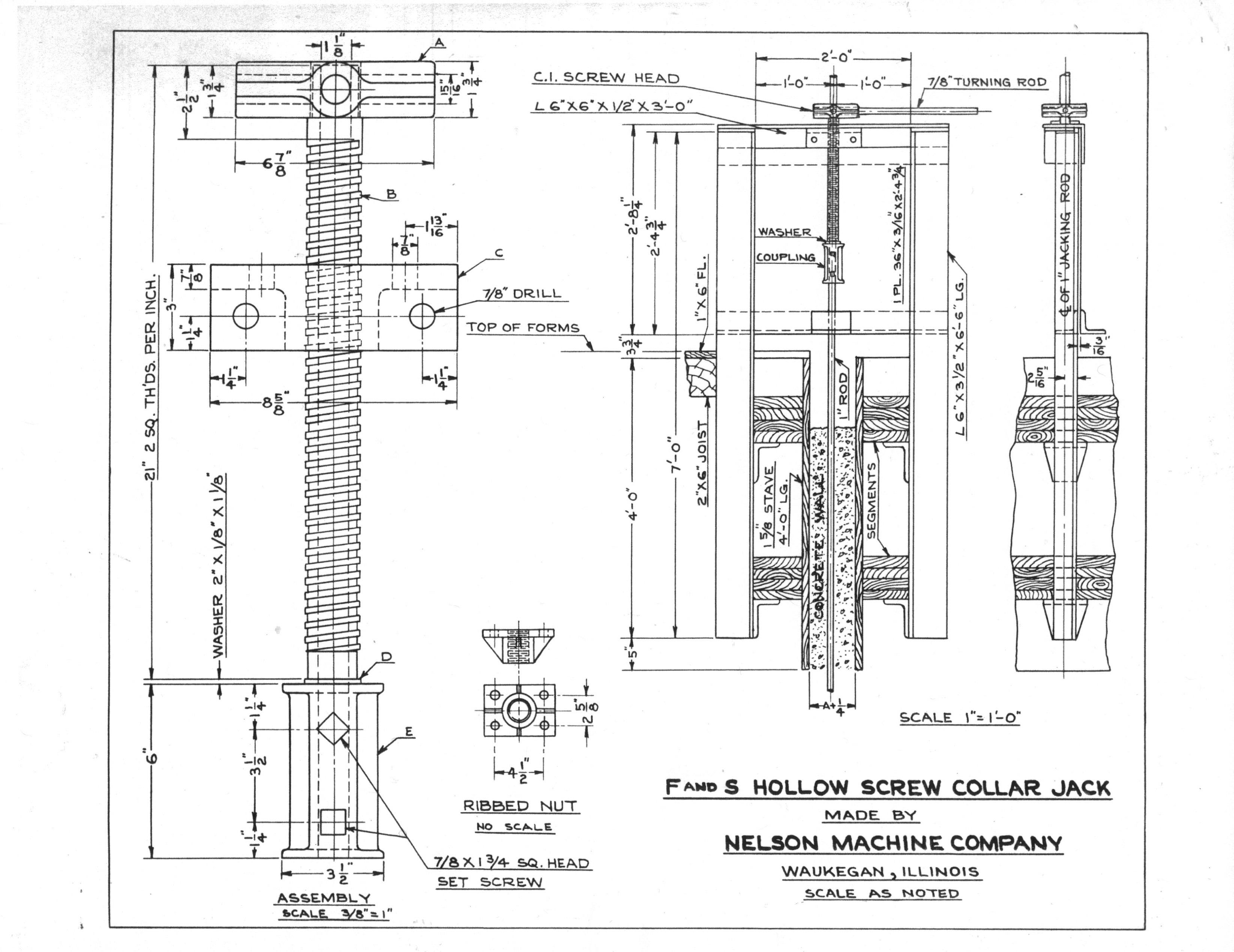

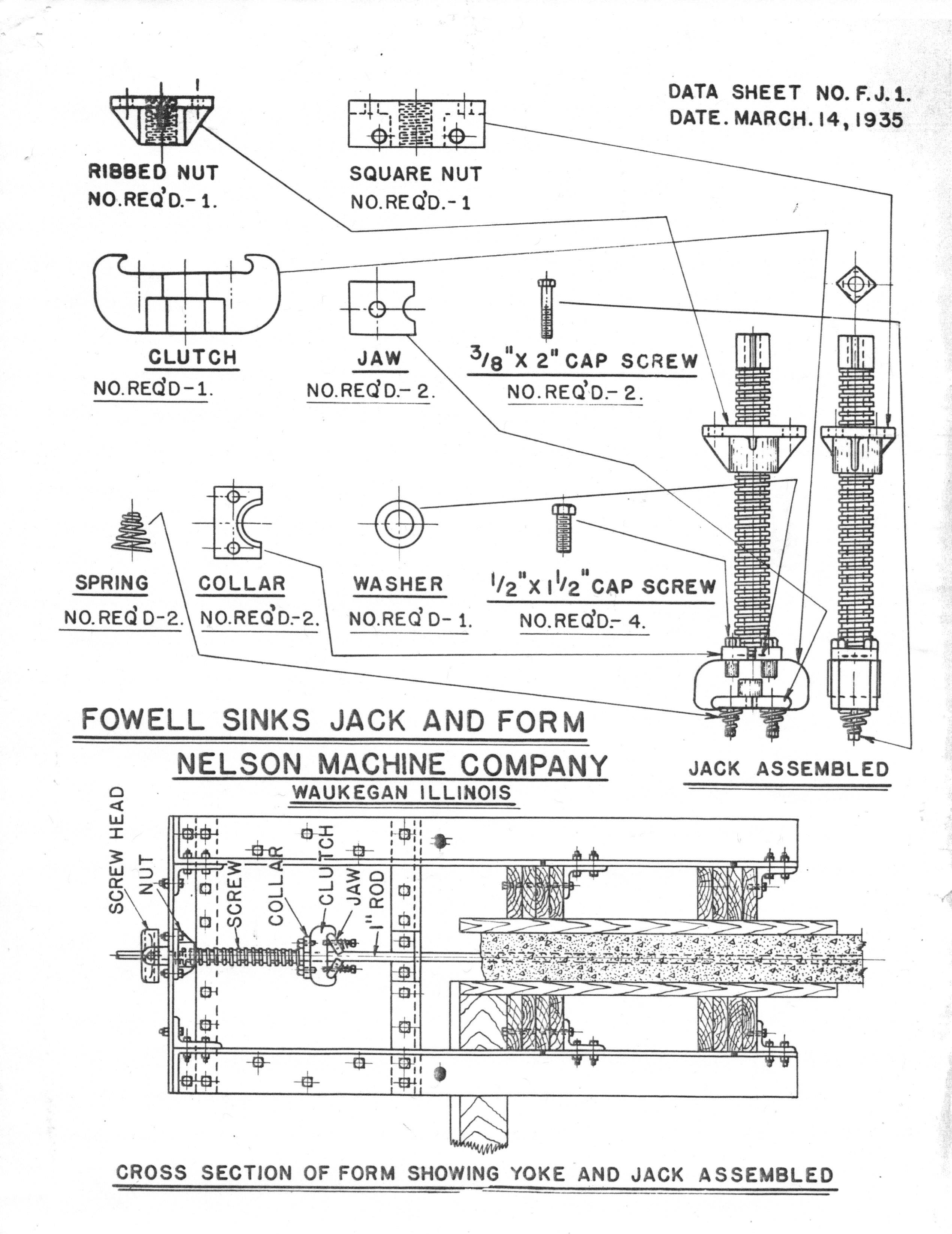

In the evenings, Mama would drive us to the job so we could watch the pour. It was like watching magic, all the lights twinkling, seeing men running the wheelbarrows (buggies) full of concrete and the men pumping by hand the jacks as the wooden, rounded slip-forms edged up. I was fascinated to see the concrete “grow” until the tanks finally topped out.

I once observed Daddy running his hands through the gravel that had just been dumped at the job site. He immediately stopped the truck and told the driver to take it all back because it was too coarse. It had to be exactly the right grade to prevent blowouts.

He often ran his hands along the tank walls as the pour was happening, knowing instinctively how the surface should feel.

As I grew older, wearing a hard hat just like Daddy, I loved being with him on the job site. I was impressed that he would stop and talk to the men who followed job to job. He knew their wives’ names and always asked about the children.

Daddy has always been my hero.