Story by Kristen Cart

Sometimes our elevator quest ends in a dead end, without definitive answers. In the case of McAllaster, Kan., we had only an old photo belonging to my grandfather, William Osborn, to go on, and Gary Rich and I never got any independent confirmation of the builder. When I went to visit the elevator two months ago, nothing was left and there was no sign it had ever existed.

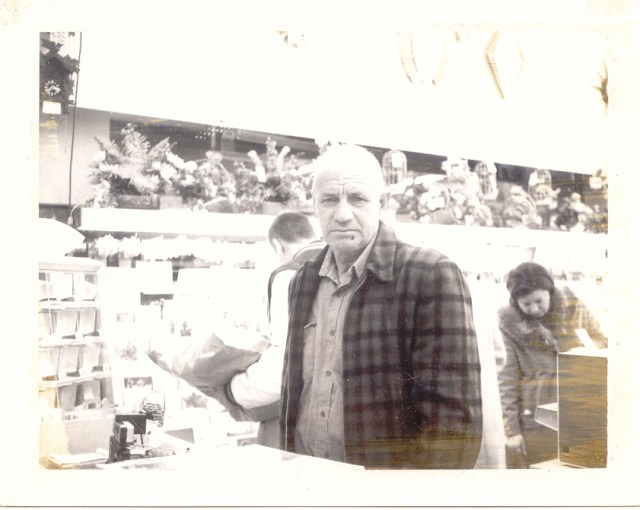

Gary Rich tried hard to get information about the builder, after he had gone to McAllaster to photograph the elevator. Both of us made calls to the cooperative. But all we were able to confirm was that it was slated for destruction sometime this year. It was shut up tight, of course, when Gary went to see it, and, no man-hole covers were visible from the outside. The only clue we could find was an old photo of one of grandpa’s projects, which was probably built for J. H. Tillotson, Contractor, of Denver, Colo., judging by the style. The caveat was that quite a few others similar to this one were also built, and some of them have long since disappeared.

Elevators like those at Daykin, Fairbury, and Bradshaw, all in Nebraska, were built in a similar style, so the only clues to their builder are external to the main house: elements such as windows, driveways, office buildings, and loading chutes can be compared to details in my grandfather’s old photos. Of course, if we have independent verification, such as contemporary newspaper accounts or my dad’s memories, it makes our lives easier, since only one of grandpa’s photos has any caption. Daykin and Fairbury have both been verified in this way.

When the photo above is compared with the photos taken by Gary Rich of the McAllaster elevator, it shows just enough difference to dash our hopes for an identification. The building behind the driveway appears to be attached, and the windows don’t match our photos of McAllaster. So we are at a frustrating impasse. We still don’t know the identity of the elevator in grandpa’s photo, and we still don’t know the builder of the McAllaster elevator, though we suspect it was a J. H. Tillotson project. With no way to verify it, we are at the disappointing end of our quest.

Related articles

- Then and Now: The J. H. Tillotson elevator at Fairbury, Nebraska (ourgrandfathersgrainelevators.com)

- In Monument, Kansas, the elevator is closed to visitors and its story sealed (ourgrandfathersgrainelevators.com)