Story and photos by Kristen Cart

The road to Traer, Kan., was a bit obscure. The town is south of McCook, Neb., across the border, on unpaved secondary roads. It took some navigating to get close to the elevator, and then to find the right road, once the elevator peeked over the farm fields. We were rewarded with a handsome, squared-up, tall elevator on a lonely rail line in a winding creek valley surrounded by farmland. I hopped out of the van in a grassy parking area and started to take pictures. A truck was parked at the weighing house by the elevator. I knew this was a private farm, and it always had a privately owned elevator, from the time my grandfather built it. So I wanted to make my presence known.

When we visited McCook’s elevator earlier in the day, worker Kelly Clapp told me the Traer elevator was still in operation. But his information was about two years out of date. Don Grafel, who greeted me when I entered the elevator office, chuckled when I asked if the elevator was working. “I wish a tornado would take it down,” he said.

Don had started working at the Traer elevator as a kid. His family now leases the farmland from a granddaughter of the Anderson family, who had the elevator built, and as part of the deal, the Grafel family had to buy the elevator. The Grafels operated it for a number of years.

The elevator was retired two seasons ago, Don said. The problem with the elevator was twofold. It had been built in a flood area with a high water table, and the measures taken during construction to account for the water had started to fail. It had leaking problems during wet years. But worse, the elevator was slow. Don said the elevator could take a semi-load at a time in the pit, which was good, but it would take an hour to load the bins. Fifteen years ago, the Grafel farm placed metal bins on high ground above the town. That handled the water risk, but Don said that even those bins were falling behind demand because of slow loading.

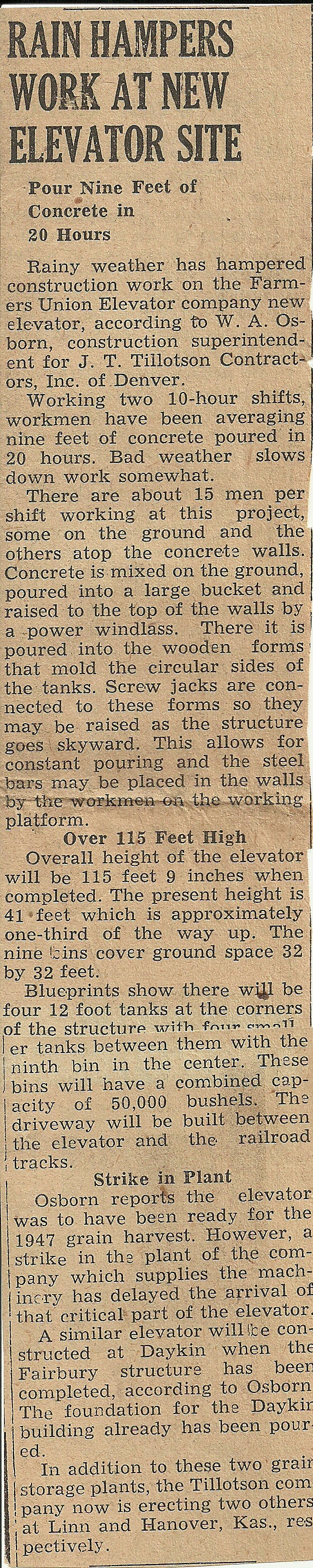

Shirley Nichols, who also worked at the office, was keenly interested in the history of the elevator. I had a treat to offer her. Russell Anderson, who commissioned the elevator, wrote a letter of recommendation for my grandfather’s new company on May 6, 1949. The Traer elevator was an example of Grandpa’s work before he went out on his own after working for J.H. Tillotson, Contractor. I gave a copy of the letter to her along with a photo my grandfather took during the elevator construction. In return, she gave me another construction photo and some historical pictures of the town.

Finally, my hungry and thirsty children came into the office, and the visit was pretty well over. Don’s brother Greg came in after meeting my husband in the parking lot. He wondered who had dropped by. But it was time to get on the road again, before the complaints got too shrill.

The good people of the Grafel farm made us feel very welcome, and gave us a window into the Traer elevator’s past. I’m glad we were able to see it while it still stands.

Related Articles

- In 1949, Mayer-Osborn built to suit Traer, Kansas (ourgrandfathersgrainelevators.com)