Story by Ronald Ahrens and photos by La Rose Tillotson

The bend on Route 92 as it entered Wahoo, Nebraska, from the east was always welcome. Here, the road dipped down and crossed Sand Creek at the edge of town, then turned into leafy neighborhoods. It was the first shade for us after more than 30 miles under the sun on the flat prairie.

Wahoo was a frequent waypoint when our family visited relatives in David City farther west.

A site of interest in Wahoo was the Saunders County Courthouse, where a torpedo was displayed near the curb. Even when I was eight and nine years old, the torpedo seemed incongruous, being so far from the sea. But we Nebraskans were starved for variety, and leftover munitions from a distant war were deemed tasty morsels.

Never did it occur to me that the Wahoo grain elevator had been built by my grandfather’s company. We knew he built elevators but assumed they were in far off places like Iowa.

Kristen Cart has already visited Wahoo and written one post.

But there’s new reason to think about the town after Aunt La Rose Tillotson drove there on a recent tour of the countryside. She forwards the pictures you see here.

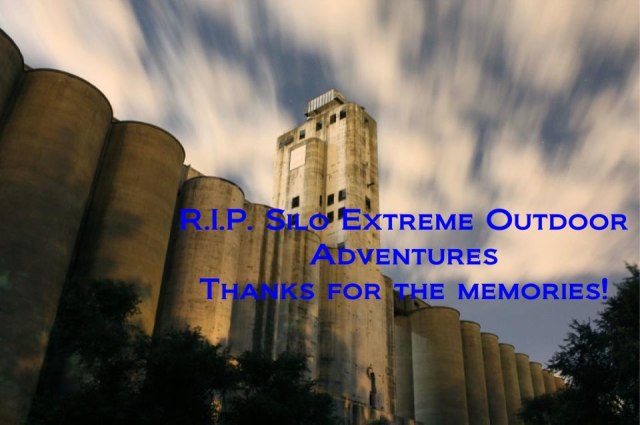

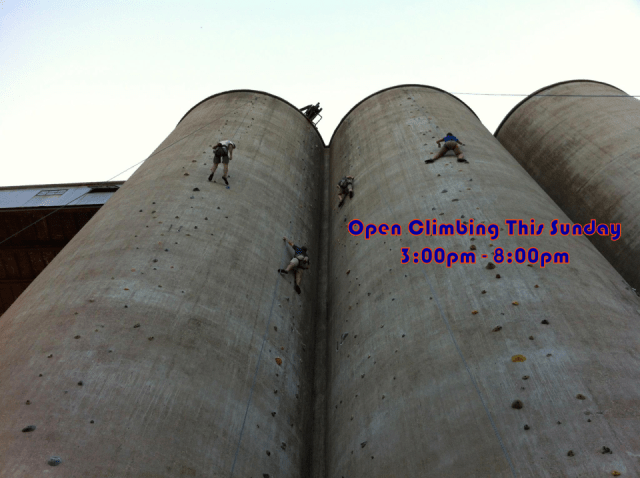

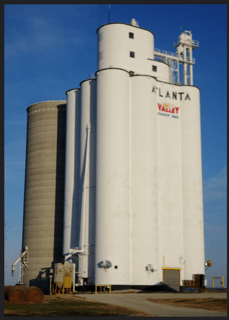

As a young woman, Aunt La Rose lived in Wahoo for a short time. While going about her daily business, she never gave much thought to the elevator that stands along North Chestnut Street between Fifth and Sixth.

This isn’t a surprise, as a form of amnesia touched many family members after the family business faded out. Grandfather Reginald died in 1960.

Here are some particulars of the Wahoo elevator:

Tillotson Construction Company used the same plan as from Imo, Okla., which had also been built in 1950. That meant a 150,000-bushel elevator rose from a 54- by 51-foot slab over a pit nearly 16 feet deep. The drawform walls were 120 feet high, and the cupola topped out after another 26.5 feet.

From atop of the Wahoo elevator, you could probably see all the way to Swedeburg, looking south, and Malmo, looking northwest. (Prague–home of Czech Heritage Days–was just a bit northwest of there.) It’s doubtful, though, you could see as far as Valparaiso, in southwestern Saunders County. Ulysses, way to hell and gone in Butler County, was out of the question.

Some other noteworthy aspects of the Wahoo’s single-leg elevator were its use of 3,056 tons of reinforced concrete and its gross weight, when loaded with as much as 4,500 tons of grain, of 8,216 tons.

I don’t see anything else in the specifications that distinguish the Wahoo elevator all that much from Imo, or for that matter, David City, which was built the next year because whatever Wahoo did had to be done in David City, too.

But no other place was like Wahoo. Wikipedia says the name comes from an Indian word for the shrub Euonymus atropurpureus, which yields arrow wood. But who believes it? I think they’re covering up for the day in 1870 when two large casks of beer fell off the delivery wagon.

Remember these four things about Wahoo:

- Wahoo Sam Crawford came from Wahoo, played outfield from 1899 to 1917 for the Reds and Tigers, and still holds the Major League record for most triples (309). He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1957.

- A wahoo (Acanthocybium solandri) is a sport fish in the tropical oceans, but as far as I can tell it isn’t the official fish of Wahoo. Lake Wanahoo is barren of wahoos.

- Wahoo was a long-running gag on Letterman.

- Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Howard Hanson (b. 1896), three-time Academy Award-winner Darryl F. Zanuck (b. 1902), and Nobel Prize-winning geneticist George Beadle (b. 1903) came from Wahoo.

How many towns of Wahoo’s size–about 4,500 souls today–have produced a Hall of Famer as well as Pulitizer Prize, Academy Award, and Nobel Prize winners?

Beyond all that, Wahoo has a Tillotson elevator.

Sometime overnight on Wednesday, May 4,

Sometime overnight on Wednesday, May 4,

My days in construction are ones I remember fondly, even though the work was hard and dangerous and the hours were long.

My days in construction are ones I remember fondly, even though the work was hard and dangerous and the hours were long.

![12144948_1082373501859277_6234689862261171471_n[1]](https://ourgrandfathersgrainelevators.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/12144948_1082373501859277_6234689862261171471_n1.jpg?w=640&h=480)