Story and photos by Kristen Cart

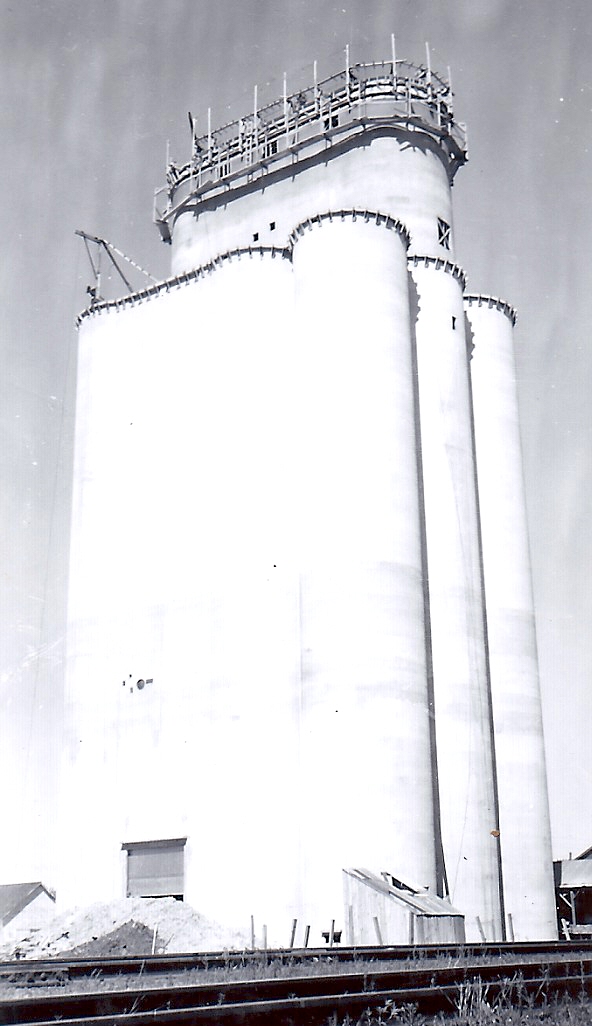

Along U.S. 6 between Omaha and Lincoln, Neb., stands an early testament to the ingenuity of the Tillotson Construction Company of Omaha. This early elevator, which rises alongside the highway next to its attached annex in the town of Greenwood, still holds grain. The original elevator was built with a capacity of 129,000 bushels. On the side facing the highway, stenciled in black, is a sign that says “Built by Tillotson Construction Co. Omaha Nebraska.” The lettering is partially obscured by paint and concrete patches.

Highway 6 is a very familiar stretch of road. I have driven it innumerable times between Ashland and Lincoln while visiting my family–on every run to Lincoln, the old Tillotson elevator and its annex come up on the right side of the road about a third of the way there. As a little girl, when traveling across Nebraska, I would see a white edifice on the horizon, and it meant a new town was coming up and we were closer to our destination. Now, living far away, I rarely see the elevators that have become so familiar. But last summer, I revisited this one.

The Greenwood elevator was built in 1951. Its annex was added in 1954, and although we do not have the construction record of the annex among our Tillotson company papers, the embossed manhole covers identify its provenance.

The pairing of a Tillotson elevator with a Tillotson annex is fairly unusual in the company records–usually another company would come along and build an annex. During the elevator boom, it seems very likely that the Tillotson company was too busy to meet the demand for annexes that were springing up everywhere, and it is very doubtful that they competed and lost the contract at each site. The company was too good at what they did, and it is almost certain that they had more work than they could accept.

We have the building specifications for the original elevator in the Tillotson Construction Company records.

We have the building specifications for the original elevator in the Tillotson Construction Company records.

Greenwood’s elevator was built following the Churdan Plan, with four 14 1/2-foot-diameter tanks, 120 feet high, and a 13 x 17-foot driveway. The spread was 13 feet, and eight bins were built over the driveway. The plan called for 17 total storage bins and a dust bin, with bin number 8 split to accommodate a dryer. The total capacity was 129,000 bushels.

Grain capacity per foot of height was 1318 bushels. For the project the company poured 1255 cubic feet of reinforced concrete, and 25 cubic feet of plain concrete for the hoppers. 60.23 tons of steel were used for construction (including jack rods). The average weight of steel per cubic yard of concrete was 96 pounds. The plans broke out the concrete and steel to be used for each line item:

Below main slab: 3,200 pounds of steel; 30 cubic yards of concrete;

Main slab: 15,870 pounds of steel; 118 cubic yards of concrete

Draw-form walls: 82,377 pounds of steel; 934 cubic yards of concrete

Driveway and work floor (including columns): 3,370 pounds of steel; 26 cubic yards of concrete

Deep bin bottoms: 3,491 pounds of steel; 19 cubic yards of concrete

Overhead bin bottoms: 3,752 pounds of steel; 23 cubic yards of concrete

Bin root: 3,060 pounds of steel; 30 cubic yards of concrete

Scale floor (or garner), complete: 186 pounds of steel; 3 cubic yards of concrete

Cupola walls: 2,789 pounds of steel; 35 cubic yards of concrete

Distributor floor: 886 pounds of steel; 7 cubic yards of concrete

Cupola roof: 1,129 pounds of steel; 9 cubic yards of concrete

Misc (boot, leg, head, track sink, steps, etc.): 360 pounds of steel; 20 cubic yards of concrete

Attached driveway: driveway extension included above

Construction Details

The dimensions of the main slab were 49 x 49 feet, with a main slab area (actual outside on the ground) of 2,377 square feet. The total weight of reinforced concrete, at 4000 pounds per cubic yard plus steel, was 2,570 tons. Also computed at 4000 pounds per cubic yard, the total plain concrete weight for the hoppers was 50 tons. The fill sand for the hoppers, at 3000 pounds per cubic yard, was 360 tons. The planned weight of grain was 60 pounds per bushel, and when filled, the elevator could hold 3,870 tons of grain. Fifteen tons of structural steel and machinery were added to complete the planned gross weight, loaded, of 6,865 tons. The elevator was designed to withstand 2.89 tons per square foot of bearing pressure.

The dimensions of the elevator were planned as follows:

The dimensions of the elevator were planned as follows:

Main slab thickness: 18 inches

Main slab steel: 1 1/4-inch square at 10-inch o. c. spacing

Tank steel and bottom for the round tanks: 1/2-inch diameter at 12-inch spacing

Lineal feet of drawform walls: 1,006 feet

Height of drawform walls: 120 feet

Pit depth below main slab: 12 feet 0 inches

Cupola dimensions (outside width x length x height): 17 x 34 x 22 feet

Pulley Centers: 145.67 feet

The elevator was designed to operate with one leg. A distributor floor, track sink, full basement, and electrical room were included in the plans. Two dump grates, 5 1/2 x 9 and 15 x 9 feet, were built. The columns under the tanks were 16 x 16 inches square, and the boot-leg and head were built of concrete.

Machinery details

Boot pulley: 60 x 14 x 2 2/16 inches

Head pulley: 60 x 14 x 3 15/16 inches

R.P.M. Head pulley: 42 rpm

Belt: 310 feet of 14-inch 6-ply Calumet

Cups: 12 x 6 inches at 9-inch spacing

Head drive: Howell 30 hp.

Theoretical leg capacity (cup manufacturer rating): 6,250 bushels per hour

Actual leg capacity (80% of theoretical): 5,000 bushels per hour

Horsepower required for leg (based on above actual capacity plus 15 percent for motor): 22 hp.

Man lift: 1 1/2 horsepower electric

Load out scale: 10 Bu. Rich.

Load out spout: 8 inch w.c.

Truck lift: 7 1/2 Ehr.

Dust collector system: fan to dust bin

Cupola spouting: 10-inch diameter

Driveway doors: 2 overhead rolling

Conveyor: none

Also built

Inside steps

Dryer provided (split bin)